Twenty-seven-year Moab Local John Williams says “I don’t think there’s any going back to how it used to be.” His tired eyes are fixed on a placid, mid-December Main Street, “Moab is on the rise and it’s going to continue to be on the rise.”

Visitors both domestic and international have come to recognize Moab as a charming place of lodging amongst the expansive almost alien landscape of eroded sandstone and red rock icons. The isolated desert community rests along the shore of the Colorado River near an overlying rim, and serves as an access point to Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, the La Sal mountains, and a seemingly endless idiosyncratic natural landscape.

While consisting of only 5,130 permanent residents in 2013, Moab accommodates over two million incoming tourists annually, generating a burgeoning tourist economy that former Moab City Councilwoman Kristin Peterson approximates at $263 million. As awareness of the peerless gem of southeastern Utah grows, so too does its commercial trajectory — with no sign of exhaustion.

Williams has owned and operated outdoor expedition and rafting company, Navtec Expeditions , since its small-scale foundation in 1987. He has experienced Moab’s profound growth first-hand, remarking that “The last two years have been the biggest in the travel industry in Moab that I’ve ever seen. Seasons are extending — we even ran trips clear through November last year.”

With the ubiquitous advertisements and trademark Delicate Arch license plates, it is easy to conceive of tourism as a tacit fact of nature in the Moab area, though that couldn’t be any farther from the truth. What initially existed in obscurity as a small-scale agricultural community mushroomed in size after the eventful early 20th century discovery of high deposits of uranium and other valuable materials, and became known near the 1950s as “The Uranium Capital of the World.”

In the early 1980s, the mines had subsided with the conclusion of the Cold War and mounting environmental concerns, leaving the once flourishing industrial community deflated and in rapid decline. Local governments stridently shifted attention to showcasing the region’s natural wonders, particularly its immense oportunities for outdoor recreation, thereby revitalizing — even rescuing — Moab for years to come. “Moab has been a tourist town since the uranium industry went under,” Williams stated, “it’s all we have — we need it here.”

Moab’s emergence as a tourist hotspot is a double-edged sword however, and many residents fear displacement as the town becomes progressively more commercialized, and thus more expensive to live in each year. To better understand the extent and implications of this resort-town transition, I travelled to a vacated, snow-covered Moab to speak with the individuals whose lives hang in the balance. Largely unoccupied in the languid lull of the off-season, these local residents were more than happy to share their perspectives.

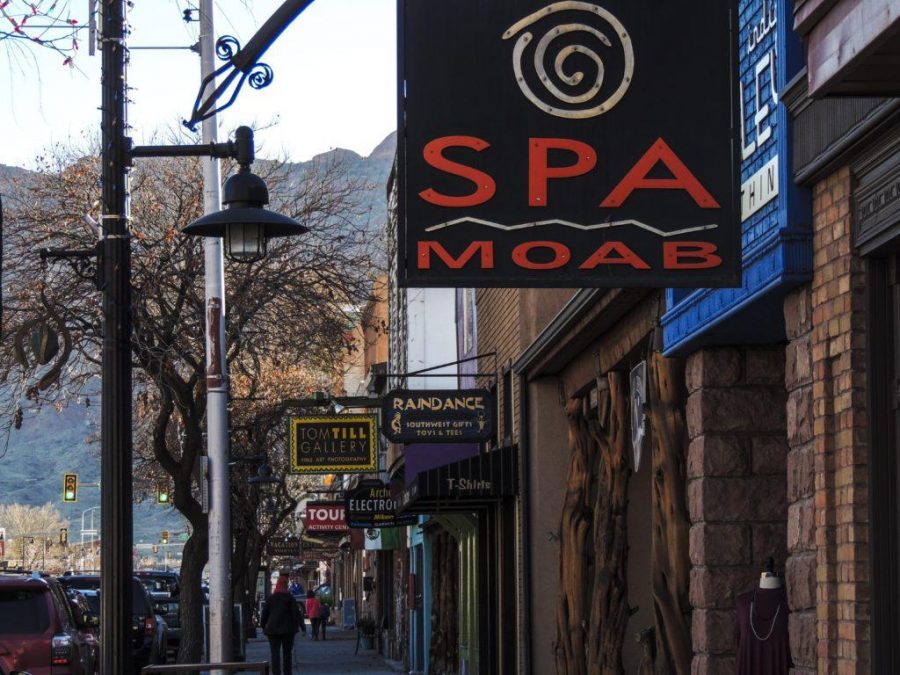

Marie, or “Moonbeam” as her friends call her, is an 11-year Moab resident and owner of Star Shine Gifts, a metaphysical gift shop on Main Street. She, like virtually every other small business owner I spoke to, notices that “the season starts earlier and ends later,” growing busier each cycle. She recognizes that “Moab is transitioning into a resort town — all that’s needed is a bigger airport.” When asked of her conceived worst-case scenario, she emphatically stated, “The worst would be the arrival of big-box retailers” similar to Walmart.

Like many locals who relish Moab’s small town atmosphere, Marie fears that monetizing the area threatens to diminish its natural tranquility.“There are things that you can’t put a price on,” she says, “like clean air, and clean water, and dark skies — peace and quiet. These are beyond priceless.”

Co-owner of Amber Waves Salon and lifetime resident, Morgi Croasmun, suggests that locals can cope with growing commercialization by working to “keep it small town,” by “supporting local businesses first and foremost.” This trajectory, she feels, is inevitable. “If we don’t keep growing, we’ll stop where we are or regress.”

When asked about Moab’s skyrocketing cost of living, she admits that it has grown tougher to afford to live in the town, “especially rent-wise. We make good money through a certain period of time when the tourists are here, but it becomes more difficult through the off-season.”

While local residents and policy-makers were successfully able to block the suffocating induction of Walmart into the town in 2007, largescale commercial developments, particularly in lodging, have multiplied in recent years. Three major hotels, two of which were commissioned by Hilton Worldwide, began construction just last year. Another major resort near the iconic Lion’s Back formation is also in the works, threatening to interfere with access to the popular Sand Flats hiking area.

More troubling still are the soaring property values and increasing cost of living — 11 percent higher than the national average and continually rising— a new fiscal environment that 73-year Moab local and former miner, D, fears is threatening his ability to live in his home town.

Exasperated, D said, “The old people that have lived here can’t afford to pay the taxes. We’re all on a fixed income now. Rent is going up every month — how the hell are we gonna make it here? We can hardly even do it now.”

Reflecting similar anxiety of Moab’s commercial future, another longtime local who chose to remain anonymous shared that she has “good friends in Aspen. The same thing that happened there, and places like Vale and Telluride, is happening here in Moab.” Low-income service workers in Moab, she projects, will no longer be able to afford to live in town, and will ultimately have to live elsewhere and commute — a lifestyle that grows less sustainable each year as the cost of living in neighboring communities like La Sal, Monticello, Blanding, and Bluff increase correspondingly. “I feel a privilege, a huge privilege, that I knew Moab before all of this.”

“That’s one of the big problems we have: housing,” Williams observes, “there’s just not enough good, low-income housing here.” While some low-income housing units do exist in Moab, many residents that I spoke to felt that it wasn’t nearly enough to adequately accommodate the town’s struggling service worker foundation as they face displacement with the encroaching commercial future.

Many locals, however, are optimistic about the new face of Moab, and feel that with proper reception it can potentially be the best thing for the town. Rebecca McAllister, owner and operator of Moab Made, recognizes that “it’s more expensive to live here, but also more sustainable. Tourism has brought a lot of job opportunities that would not be here otherwise. It’s built the economy, and allowed people to live in the middle of nowhere.” Her business is representative of coexistence and cooperation with Moab’s new direction, exclusively selling the work of over 75 local artists.

She, like many other Moab locals, have come to accept the inevitable, and “rather than using our energy to fight it,” she says, “we should spend our energy on handling it wisely and gracefully.”

Moab’s growing tourist dimension seems to be elapsing other, less sustainable uses for the better, as the Bureau of Land Management has just last month declared 451,000 acres protected and non-leasable, preventing surface disturbance like mining or oil drilling in scenic areas such as the Moab Rim Trail, Corona Arch, and Indian Creek.

Although John Williams has observed the severe impact as a result of increased recreational activity, he feels that many tourists “just don’t know what the dos and don’ts are — they wouldn’t do it if they knew better.” Cherishing, rather than exploiting, Moab’s natural resources for monetary gain may be the key to conserving the region as it progresses into the future, as long as the land is treated responsibly and consciously.

Whether this encroaching Aspen-ization of southeastern Utah’s luminescent desert oasis is the area’s conservational salvation or a mechanism for displacement and gentrification is uncertain, but “the future is upon us,” Williams says, “and we have to embrace and deal with it the best we can.” Only time will tell if Moab’s small-town infrastructure and delicate natural environment can cope with the demands of its emerging epoch. This seasoned local warns, “there’s a certain limit to what we can carry here, and we’re getting pretty close now. We are going to have to adjust.”