The southeastern corner of Utah has seen numerous changes over the past year as Bears Ears National Monument was first established and successively shrunk. Although the battle over the borders has been steadily building since 2010, the history of Bears Ears dates back to long, long before this.

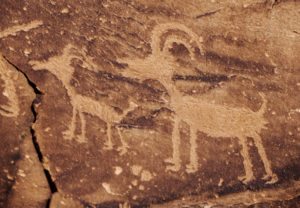

The first people to inhabit the Bears Ears region were the ancestors of modern native tribes. They existed here for thousands of years before the first Mormon settlers reached the region, and have a history as complex as any other civilization. Understanding all the intricacies of this history is a job fit for a full team of archaeologists, but — fortunately — the important points are simple.

Because multiple tribes lived in this area throughout its history, today tribes that no longer reside in Utah still have important ancestral connections to the land, and all these ancestral people left behind hundreds of thousands of artifacts that now scatter the Bears Ears region. This means that modern tribes, like the Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Ute Indians, and Navajo, have strong cultural, historical, and spiritual ties to Bears Ears.

The next main inhabitants of this region were the Mormon settlers. In 1879 they set out on the infamous “Hole in the Rock” journey to settle the then barren area near the San Juan river. Though they encountered and fought against numerous obstacles, including blasting a 2,000 foot passage down to the Colorado river in order to cross it, the pioneers made it without any loss of life. By 1880 the road was open and the settlement of Bluff had begun. Since then, Bluff and other settlements near Bears Ears, like Blanding and Monticello, have grown into proper towns and seen generations of families carve a living out of Utah’s sandstone deserts.

Unfortunately, these two groups that both have historic and cultural claims to the land, do not see eye to eye on how to use it. The current inhabitants of Blanding, Bluff, and other border towns have grown up exploring the wilderness around them and using it to graze cattle. They’ve been free to roam relatively unrestricted and even collect or sell many of the artifacts they find. To them, this is life. Changing it would be enormously difficult. The tribes, however, see the destruction that is happening to their ancestral lands — mostly in the form of large-scale looting of and vandalism to the artifacts there — and are not pleased.

This is why the Navajo, in June 2010, presented the first proposal to protect Bears Ears to Utah Representative Bennett. The Navajo went around speaking to all the elders of the Navajo nation and other tribes with interests in the area to create a map of all the areas that needed protection. Representative Bennett lost his election that year so the Navajo did not release their map until April of 2011. In July of that same year, Utah Dine Bikeyah (UDB), a Navajo organization set up to specifically handle the process of protecting Bears Ears, turned the map and proposal into a short book and distributed it to political leaders across Utah and Washington D.C. The idea of protecting Bears Ears was now fully on the table, and the debate began.

It took two more years before the state of Utah had a real proposal in response. It came in the form of the February 2013 Utah Public Lands Initiative (PLI). The bill, proposed by Utah Representative Bishop and supported by Utah Representative Chaffetz, sought to solve many of southern Utah’s land debates in one giant compromise. The peak of this was Bears Ears. The tribes, now aligned in the Bears Ears Intertribal Coalition, wanted Bears Ears to be protected at a size of 1.9 million acres, with the authority to manage the land placed in their hands.The state of Utah wanted to ensure that the people of Bluff and Blanding had their interests represented as well, and wanted to keep the area open to future economic development.

Although nearly three years of debate, discussion, and compromise went into the PLI, it ultimately failed. The tribes eventually pulled their support from the bill, saying that Representative Bishop was continually unresponsive and in the end excluded the tribes from having management authority over the Bears Ears region. By the time the 114th Congress had ended in late December 2016, no vote had been taken on the PLI.

The tribes knew that this was a possibility from the beginning, and so, planned for a backup. They initially sought to have the region protected as a National Conservation Area with the help of the state of Utah (this was the PLI), however, they also knew that the president could establish a National Monument and protect Bears Ears without the state’s help or consent. The Intertribal Coalition had therefore been lobbying President Obama and Secretary of Interior Sally Jewell in case the PLI were to fall through. When it became clear that the PLI would not gain the votes it needed before the end of the 114th Congress, President Obama designated a 1.35 million acre chunk of land in southeastern Utah as Bears Ears National Monument, and granted the tribes’ request for management authority.

The Utah delegation, and many Utahns near the new monument, saw this designation as an obvious abuse of the Antiquities Act, the 1906 law that allowed presidents the authority to create national monuments, and a huge overreach by the executive. Almost immediately, the Utah delegation began lobbying president-elect Trump. Senator Hatch was so influential in this lobbying that Trump mentioned him on multiple occasions while discussing the monument.

The first step by the Trump administration in the Bears Ears conflict took place in April of 2017 when Secretary Zinke began touring and evaluating all the monuments designated in the last 21 years. The entire process was wrapped in suspicion, however, as Zinke’s final report on the monuments was not officially released until long after the tour was complete.

On December 4, 2017 President Trump travelled to Salt Lake City to once again use the Antiquities Act to determine the borders of Bears Ears National Monument. This time, however, the monument was reduced by roughly 85%, from a size of 1.35 million acres to 200,000 acres. Grand Staircase-Escalante, a monument designated by Bill Clinton just shy of 20 years ago, was also reduced from 1.9 million acres to about a million acres. The reductions were met with applause from the Utah delegation, and boos from thousands of protesters who took to the Capitol steps a few days before Trump’s arrival.

Across the country, the reductions were met with the same mixed reaction. A bigger question plagued the action: was it legal? The Antiquities Act does not explicitly designate the president the power to reduce monuments, though borders have been altered on a few occasions in the past. Now, the courts will decide the fate of both Bear Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante as the Intertribal Coalition and a collection of environmental groups have sued the president.

The Utah delegation, not willing to leave their victory in uncertainty, have proposed two bills to codify the president’s reductions. Representative Stewart introduced H.R. 4558, which will solidify the borders and create a new national park in one of the monuments’ sections. Similarly, Representative Curtis introduced H.R. 4532, which also aims to codify the reductions to Bears Ears. The bills are being deliberated over in a congressional subcommittee now.

The history of Bears Ears is complex, and the debate is far from settled. As the court cases and legislative pieces progress, the possibility of Bears Ears borders once again being altered is high. There only seems to be one thing certain about the landlocked, arid corner of Utah: it has made, and will continue to make, big waves.

Cover photo courtesy of Gary German.