Just four hours south of Salt Lake City lies the birthplace and holy land of one of the most versatile adventure sports today: canyoneering. Since the late 1970s, Southern Utah has hosted a select group of adventurers as they climbed, swam, and rappeled their way into the depths of the narrowest, toughest, and most fantastic canyons on Earth. Ironically, the sport of descending got its roots from a group of dirtbags focused on ascending.

Climbing had just a two-decade head start on canyoneering, with the first ascents of Half Dome and El Capitan both around the late 1950s. Soon, pioneers in the climbing community began creating their own gear for the sport. Companies like Patagonia and The North Face found their beginning at the base of Yosemite’s big walls and were some of the first companies to produce advanced climbing gear.

Most of the pioneering canyoneers started out as climbers, utilizing recently developed climbing equipment to go down instead of up. Pitons were used to bolt un-anchorable rappels, and climbing ropes lowered the early athletes over waterfalls and overhanging cliffs. But canyoneering did not truly have its own identity like climbing did. It was more an activity for climbers to do in their off time than a sport in its own right.

Dennis Turville — climber, professional photographer, and pioneering canyoneer — changed this in the 1970s. Often accompanied by fellow outdoorsmen Mike Bogart and a few other close friends, Turville blazed the trail for many of the first recorded descents around the Zion area. He is considered one of the earliest serious recreational canyoneers. Famous Zion canyon routes like Heaps, Keyhole, and Pine Creek are all can be attributed to Turville and company. His reports are sparse — usually no larger than a paragraph for each canyon. Sometimes, like in the case of Middle Echo Canyon, the account is as short as, “one rappel bolt.”

The records are as barebone as they come, yet this was likely intentional. Turville didn’t record his canyons so others could follow him. These few lines were simply him documenting that he was the first down the canyon. He wanted his hidden hobby to remain that way. As it stood, he never saw other people in his canyons, or even signs of people. The only information that slipped to the public’s eyes were the photographs Turville snapped inside the canyons, offering glimpses into the tantalizing world beneath the rim. Yet, the locations of these photos were heavily guarded.

As sparse as they were, the reports at least included a date for each canyon. The earliest of which, and possibly one of the first true American canyoneering descents ever, was the Middle Fork of Choprock in April of 1977. It was descended by Bogart, Karen Carlston, and Dave and Annie George. Because of its non-technical nature, Turville sat out, preferring instead the difficulty and technicality of other canyons.

Revealing Hidden Canyons

Turville and his associates kept pounding out first descents into the late 1980s, but by now they were no longer alone. Other explorers started dropping down canyons all over Southern Utah and beyond. Among these were a few who believed the canyons should be for all.

Michael Kelsey, by far the most controversial of the above mentioned group of canyon-goers, wrote some of the earliest guidebooks for canyoneering. His most popular, “Non-Technical Canyon Hiking Guide to the Colorado Plateau,” just published its sixth edition and boasts over 400 pages of route descriptions.

Although many people use Kelsey’s descriptions to find new adventures, not all are fans of the man. In fact, enough people find Kelsey despicable enough that he acquired the nickname “the devil in sneakers.” This contempt stems from a few perspectives.

On one hand are the Bureau of Land Management/National Park Service (NPS) agents who now have to deal with much higher traffic in previously unknown areas. This inevitably means an increased number of ill-prepared parties and a much higher rate of accidents and rescues. It also means greater environmental degradation.

The other half of Kelsey’s critics are the serious outdoorsmen who recreate in Southern Utah and like Turville, aim to keep their spots secret. Suddenly, their favorite local hike is frequented by troops of boy scouts and trails appear where footprints weren’t visible a few years ago.

Kelsey, who has been catching flack since he published his first canyoneering book in 1986, shakes most of the blame onto individual parties for not practicing Leave No Trace principles or preparing properly. Since then, he has continued to hike, take meticulously detailed notes, and publish edition after edition of his various Southern Utah guides, opening up the world of canyoneering to anyone with $20 and a sense of adventure.

Canyoneering Hits the Mainstream

By the early 1990s, canyoneering had grown in the Southwest among small groups of serious outdoor recreationalists. However, it had yet to reach the mainstream in any impactful way like climbing had. Unfortunately, canyoneering became mainstream after the stories of two accidents.

In 1993, a group of three adults and five teenagers faced devastation in Kolob Canyon near Zion National Park. Flood waters were too high for the canyon that day and two adult leaders drowned. The remaining six were trapped for days in the canyon before the Park Service rescued them.

The ordeal gained public attention when some of the survivors sued the NPS and the Washington County Water Conservancy District, for the death of the two men because their leaking dam upstream of Kolob attributed to some of the heightened flood waters. The tragedy and controversy of the story, and the implications of the outcome of the court case on the NPS as well as landed the gruesomely tragic tale on pages from local magazines like High Country News, to national publications like People magazine. For many Utahns, it was the first they heard of canyoneering.

Just 10 years later in 2003, Aron Ralston pinched his arm in by a loose boulder in Blue John Canyon. He survived over five days in the canyon before amputating his own arm with a low quality knife and walking out. His heroic story was most famously told in the 2010 Academy Award-nominated film “127 Hours,” in which Ralston is played by James Franco. This was canyoneering’s most mainstream appearance yet, and the story most recreationalists point to when describing what the sport is to their unknowing friends.

While both of these instances spread canyoneering past the confines of the Utah desert, they also marked the sport as dangerous. If unprepared and uneducated, there are few more dangerous activities than rappelling down 60-foot waterfalls and swimming through hypothermic waters.

Legitimizing the Sport

Stories of danger and disaster seemed to only embolden more and more adventurers to get out and canyoneer. By the turn of the century, more and more people wanted to get their fix of Utah’s famous canyons, yet there was no organization in place to provide the proper education to these adventure seekers. It was shaping to become a serious problem for canyoneering. Fortunately, the solution arrived, and his name was Rich Carlson.

If Turville is the pioneer recreationalist, and Kelsey the pioneer route publisher/popularizer, Carlson is the pioneer professional for the sport. Carlson has been dropping down Utah’s canyons since the late 1970s, and started America’s first professional canyoneering guide company in 1990. In 1999, he started his ultimate vision of creating the world’s premier canyoneering organization, the American Canyoneering Academy (ACA).

David Tigner, head of the University of Utah’s canyoneering program, calls Carlson a “pioneer of canyoneering” who chose to “concentrate on training people.” His ACA today sets the bar for every canyoneer and canyoneering organization in the United States, and possibly worldwide. It is Carlson and the ACA who are responsible for deciding the requirements needed, from professional certification standards to defining a minimum degree of competency for a canyoneer.

Tigner’s own program at the U is modeled after the three basic skill sets the ACA requires for beginning canyoneers. It emphasizes practice, preparedness, and caution. One of the key points Tigner tries to impress on all his students is, “the best place to learn canyoneering is at home, not dangling 100 feet off a cliff.” This very much aligns with Carlson. He’s interested in revolutionizing the sport through training and organization, something canyoneering badly needs, rather than exploration.

The advent of the ACA in 1999 pushed canyoneering to a new level. Suddenly, the sport had legitimacy. Serious canyoneers could focus on professional guiding to earn a living rather than dirtbagging it in a van, and beginners to the sport had a place to go to safely participate and learn the skills. Yet, no matter the skill of the canyoneer, they were still going into a canyon with gear made for climbing.

Industry didn’t catch up with the sport until the mid 2000s, when Tom Jones started Imlay Canyon Gear. This was one of the first canyoneering-specific companies, specializing in packs, ropes, and rope bags. Generally, the problem with using climbing gear in canyons is durability.

While in a canyon, any given piece of gear will be submerged in water repeatedly, drug through sand, scraped on walls, and tossed anywhere from 10 to 100 feet onto the ground. This means ropes need to be more tightly woven, packs have to have drainage holes in the bottom, harnesses, as Tigner jokes, need to have a, “PVC cover for your rear end so you don’t rip out your pants.” While canyon-specific gear is still very niche and rare, even having a market large enough to support a canyoneering company is a sign of growth.

Today, the sport is a far cry from where it began. It is organized, detailed, and far safer, yet no less adventurous. Pioneers like Turville, Kelsey, and Carlson have all progressed the sport in radically different ways, blazing the path for many others to follow down the depth of Utah’s, and the world’s, best canyons.

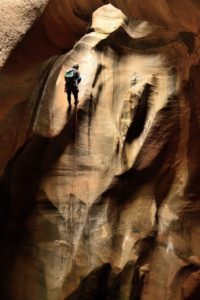

Photo courtesy of @surfnsnowboard