Skiing has held its place as the centerpiece of the Wasatch mountains for quite some time. Thousands of people come from all over the world to enjoy the slopes each winter, and their visitations play a huge role in supporting Utah’s economy. But there was a time before beautifully manicured slopes, lift access to thousands of skiable acres and a plethora of options for après ski wining and dining. Skiing began as a purely practical mode of transportation for getting around mountain towns, and evolved slowly but surely with new disciplines, technology, and resorts to become the hub of recreation and fun that it is today. Follow along to explore the origins of skiing in the Wasatch mountains, in a far more rugged and unpredictable time.

Skiing developed here in the Wasatch the way it did in most places: for winter trade. As early as the 1800’s, trappers and miners used skis to get around and complete their day’s work during the winter. Research in the Naturalist Program at Utah State has shown that skiing became an essential survival tool in the mining towns of the Cottonwoods such as Alta and in the Wasatch back, now known as Park City. One of the earliest records of skiing in Utah was in 1870 when the postman in the town of Alta reportedly traveled his delivery route on skis in winter months. It is presumed that skis made their way to the Beehive State from European countries such as Norway during this time, and were mostly intended for both uphill and downhill use for trade purposes.

The surge of mining activity in Utah was triggered by the transcontinental railroad which was finished in 1869, and made transporting large quantities of ore possible for the first time in the area. Among an entire state of mining towns, the Wasatch held two of the biggest silver producers, between the town of Alta and Park City. From 1870 to the turn of the century, more than half of Utah’s mineral output consisted of silver, and Utah produced about twenty percent of the entire nation’s silver. During the late nineteenth century, visitors of the state sometimes described Utah as one big mining camp, with Salt Lake City serving as its Main Street.

Utah’s prosperous mining activity thrived from its cultivation in the 1870’s all the way until the value of silver plummeted during the Great Depression. The economic downturn left Utah residents searching for alternatives to find wealth in a place that once flourished with opportunities. In 1936 the world’s first chairlift intended for recreational skiing was installed in Nebraska, and was based on a mechanical design used for ‘banana lifts’ in central America. It did not take long for the Wasatch mountain inhabitants to offer a response by installing cable tows at Brighton in 1937, followed by the iconic Collins chairlift in the town of Alta in 1938. The Collins lift was manufactured from leftover mining hoist parts, and ran skiers twenty-five cents per ride in the 1938-1939 winter season. While leftover mining equipment may not sound like the most secure methodology for transporting skiers to the top of a mountain, it was the equipment used on the descents that appears even more daunting to most.

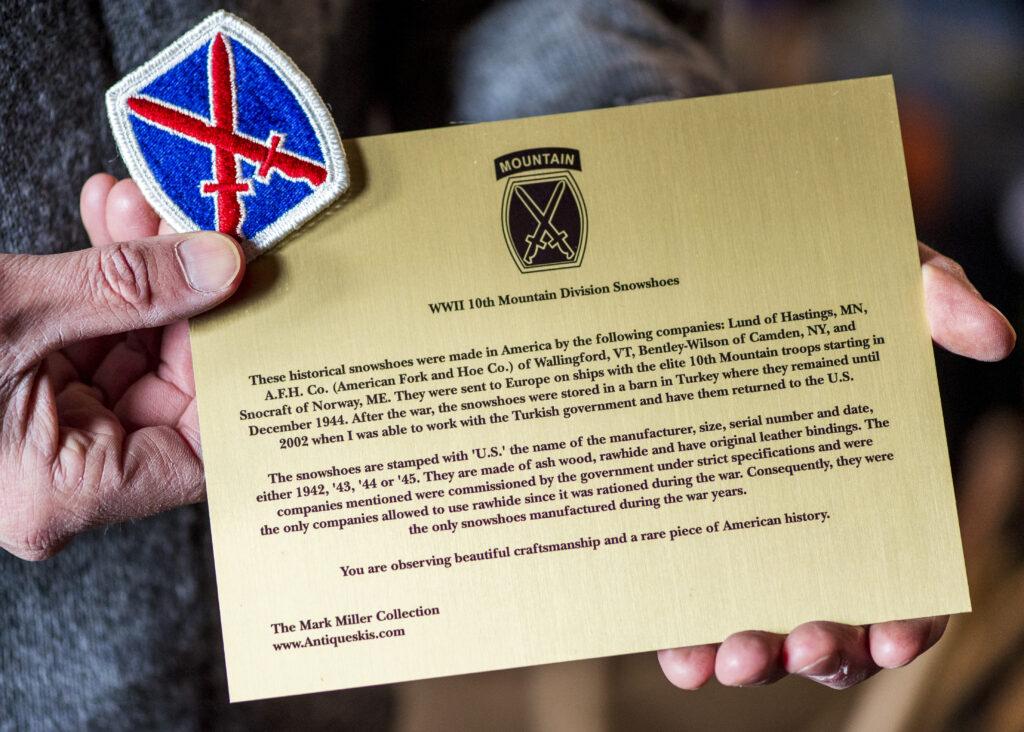

I was able to catch up with a Park City local and antique ski collector, Mark Miller, in hopes of gaining some perspective on old ski technology. Mark’s antique business, The Mark Miller Collection, boasts thousands of pairs of skis sold in a handful of different locations including the Southwest Indian Traders shop on Main Street in Park City. Mark’s collection consists of skis dating as far back as the late 1800’s and includes boots as well as poles. In the late 1800’s, skis were almost solely used for ski touring across Europe, as well as in the handful of isolated areas where skis were used in the United States. Skiing was primarily used for transportation at this time, usually for trade such as mining, as well as for collecting tree sap and trapping. These touring skis were edgeless, wooden, and often well over two-hundred centimeters in length.

The skis were generally quite practical for getting around, but could not be used for pushing the limits in any kind of high alpine terrain. The committed downhill ski came about in the early to mid 1900’s, when lift-accessible commercial skiing started to gain traction. This time period beginning in the 1930’s was the catalyst for alpine ski technology as we know it today.

Mark explained that the biggest technological advancement of ski technology in the mid twentieth century was the bear trap binding. This binding was the first to hold the toe of the ski boot in place using metal slots, and the leather strap holding the heel in place could be held to the ski, or left free to make getting around in flat spots a bit easier. The heel strap made it possible to lock the heel down to the ski for a true downhill oriented feel, while still giving the free heel option to the skier for walking around. This leather heel strap is what gave the binding its name, reminiscent to the rounded ‘U’ shape of a metal bear trap. This rigid style of binding combined newly conceived metal ski edges began to make lift access alpine skiing far more approachable and progressive. These advancements, however, came with some drawbacks and complications. Mark explained that the leather ski boots were far from warm, and made it hard to be out in the mountains all day. Metal ski edges had to be installed by hand with ten to twenty screws per ski, and meant that ski manufacturers were lucky to finish ten pairs of skis in a day. But people still skied, a time tested ideal that set the tone for skiers in the Wasatch for years to come.

By the time the 1960’s rolled around, there were American ski films, Squaw Valley had hosted the Olympic winter games, and the U.S. military had ski battalions known as mountain divisions. America fully embraced ski culture and Utah was at the heart of it all. By 1965, Park City Mountain Resort had opened, and was even featured as one of the best ski runs in America in a Sports Illustrated issue from 1966. Meanwhile, plots of land adjacent to a now well-established Alta Ski Area were being developed, and by 1971, Snowbird was open to the public with the first aerial tram in Utah. Skiing was coming to the mainstream; the UTA busses added Snowbird, Alta, Solitude, and Brighton to their routes and releasable ski bindings came into play. By the 1980’s, extreme skiing was in and names like Mike Mendenhall and Jimmy Collinson started to rack up first descents on famous peaks like Mt. Superior and the Pfeifferhorn. By the 90’s, Chuting Gallery author Andrew McLean joined in on the fun, and as the backcountry ski gear progressed, skiers were able to knock off more and more ski-mountaineering style descents, many of which required ropes.

On the other side of the spectrum, the 1980’s were huge for ski racing in the Beehive State. Dozens of Utah natives, including Roxann Toley and Steve Bounous, raced the World Cup circuit and on the American Olympic team. The ski team from Brigham Young University made their way into the National Collegiate Ski Association, and after winning a few titles made it to the NCAA. Between 1981 and 1988, the University of Utah Utes won the NCAA title five times in seven years, only to be edged out by Vermont in 1989 by a handful of points. All the while, Utah resorts began to allow snowboarders to ride the lifts, Sundance Film Festival began to bring thousands of tourists each winter, and the Wasatch mountains solidified their place as one of the premiere ski destinations in the United States.

Moving forward to the 2000’s, Utah has become quite the winter tourist scene, which local skiers are all too familiar with. Since the Olympic Winter games in 2002, tourism spending has gone up two billion dollars in the ten years following the games. After Park City Mountain Resort and Canyons Resort combined in 2015, it became the single largest ski area in the country, boasting 7,300 acres of skiable terrain. Utah contains 14 ski resorts, nine of which are within an hour from the Salt Lake City International airport. In the 2016-2017 winter, Utah was the most visited state for skiing in the entire country.

While Park City takes most of the tourists, the resorts of the Cottonwood canyons are becoming more and more crowded, and there is serious talk of a mandatory toll-booth style fee at the mouth of the Cottonwoods that could be in effect next winter. On one hand, many locals are disgusted by the idea of paying even more to participate in an already exceedingly expensive sport, but others are looking forward to tolling as a way to promote sustainability. A toll fee would be the most persuasive strategy yet for promoting carpooling up the canyons, and certainly the most effective in actually limiting the number of cars making the weekend trek. Onward, it is important for not only Utah residents, but also for the tourists to make steps towards both conservation and sustainability here in Utah. Climate change has had a nasty effect on the winters here in Utah, and many long term residents have informed me that the winters used to bring colder temperatures and deeper snow packs. Protect Our Winters (P.O.W.) is a group of climate activists with a snow sports mindset that hopes to make a difference in protecting our earth’s climate, specifically through practices for skiers and snowboarders. Follow their social media accounts to get involved, and keep winters cold around the world. If history has told us anything, it’s that the skiers of the Wasatch will do whatever it takes to keep on skiing.

References

Bradley, T. (2010). Steep Skiing in the West – A Look Back. Utah Adventure Journal . Retrieved from

http://utahadvjournal.com/index.php/steep-skiing-in-the-west-a-look-back

Butz, A. (2010). Park City’s History. Historic Park City Utah . Retrieved from https://historicparkcityutah.com/news/park-citys-history

Grass, R. (1990). For Skiers, 1980’s Were The ‘B’ Years. Deseret News. Retrieved from

https://www.deseretnews.com/article/80101/FOR-SKIERS-1980S-WERE-THE-B-YEARS.html

Heaton Jolley, F. (2015) Utah Ski Resorts by the Numbers. KSL . Retrieved from https://www.ksl.com/article/34044209/utah-ski-resorts-by-the-numbers

Hullinger, J. (1994). Snowbird. Utah History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.uen.org/utah_history_encyclopedia/s/SNOWBIRD.shtml

Lund, M., Et al. (1999). Timeline of Important Ski History Dates. International Skiing History Association . Retrieved from https://skiinghistory.org/history/timeline-important-ski-history-dates

McCormick, J. (1988). Silver in the Beehive State. Utah History to Go . Retreived from https://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/mining_and_railroads/silverinthebeehivestate.html

Larese-Casanova, M. (2014). Utah’s Rich History of Skiing. Wild About Utah . Retrieved from https://wildaboututah.org/utahs-rich-skiing-history/

Smarden, A. (2019). Utah’s Olympic Legacy: The Impact of the 2002 Winter Games. How the Games Affected Utah’s Economy. Kuer 90.1 . Retrieved from https://www.kuer.org/post/utahs-olympic-legacy-impact-2002-winter-games-how-games-affecte d-utahs-economy#stream/0

Tim Nelson

Apr 8, 2025 at 6:14 pm

Great article and about skiing in UT. Must correct your statement that the first chair lift in the world was in Nebraska in 1936. Nebraska? Really. Sun Valley, ID, yes. Anyway first one was in 1908 in Schollach, Germany.

Deborah de

Feb 1, 2025 at 2:50 pm

Nice pair of Northlands! My grandfather was the New England ski rep for Northland from the time of skiing in the 20s until the early 60s. I have a lot of his “salesmen’s samplers” which are very cool. In addition the posters he gave away to stores, catalogs and other items. Very nice article, thanks.