Stepping foot onto the Bonneville Shoreline Trail on a sunny Saturday afternoon means running into about as many people as you would at the grocery store on Thanksgiving Eve. But instead of people frantically sprinting between aisles, eyeing their list to check off every item, you’ll see bikers, hikers, and runners with child-like grins, breathing the fresh air of the Wasatch foothills.

Few would deny that nature is good for the soul, especially in a state where outdoor recreation brings in $12 billion in consumer spending and generates 122,000 direct jobs. Utahns love spending time outdoors. But recently, researchers, medical professionals, and therapists are showing that there is more going on in the body and brain than we might think, and they are beginning to see lasting effects on some patients.

UNPLUG AND REWIND

David Strayer, a professor of psychology at the University of Utah, began to study the effects of nature on the brain a few years ago, after noticing changes in himself when going outdoors.

“If [you] go on a river trip or a backpacking trip and are away for a while, you start to really think differently. Your senses are recalibrated, you notice things that you didn’t notice before,” he says. Now, he brings his classes away from technology and into the wild every year, measuring electrical activity in the brain with EEG scanners. What did he find? Nature boosts problem solving abilities, creativity, sense of well-being, and decreases stress levels and blood pressure.

When we are outside, away from our smart phones and email and the constant nagging of tasks in the back of our minds, we can rest the part of the brain that controls multi-tasking. The prefrontal cortex, as it is called, is like a muscle. It needs to rest and heal in order to give 100 percent later on. The glucose and glycogen energy stores are restored when you can quiet this part of the brain and go to default mode. It’s not that your brain just slows down though. The brain is actually more active, but in separate areas, like those activated by meditation.

Strayer can prove nature’s healing properties on a screen, but he’s also seen it firsthand. Enrolled students in his “Cognition in Nature” courses are frequently those returning from Afghanistan and Iraq after being on military tours. These students are often quiet and separate from the class, disconnected from the rest. But, as the trip continues, he sees them inch closer to others during group time and participate more and more.

“In one case, we came back to class the day after we got back from the desert and we all thought, ‘Who’s this guy sitting in the class?’ He had shaved off his beard and completely transformed. These are amazing transformations, and it happens on a regular basis.”

HEALING OUTDOORS

Psychologists and therapists are begginning to catch on the trend. At the National Ability Center in Park City, Craig Bryan, executive director for the National Center for Veterans Studies, runs a therapy program for PTSD victims that combines trauma-focused therapy sessions in the morning and recreational activities in the afternoon. While outdoor recreation alone doesn’t often have long-term recovery effects, therapy sessions and the outdoors are the perfect match.

“We use these outdoor activities for people to do things that elevate their mood. We provide opportunities to challenge the core beliefs of our veterans. Many of them ony think ‘I’m a failure. I screw everything up,’” he says. “In therapy we say, ‘Didn’t you just climb to the top of a mountain yesterday? How is it possible to climb a mountain if you can’t do anything right?’”

Since its start last year, the program has seen a 73 percent recovery rate of PTSD by the end of the two-week program. They are continuing to gather data in order to prove to the mental health community at large that there is some kind of healing power of the outdoors.

Wilderness adventure therapy can help those with other mental health issues too, be it trauma survivors, teens with mental disabilities, or addicts. At some colleges, like Prescott College in Arizona, there are even adventure therapy majors available for students. Utah boasts perhaps the highest quantity of these therapy services.

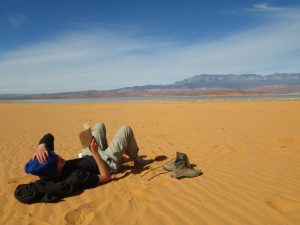

Aspiro is one of these, taking teens on trips for eight to 12 weeks all over the state. Year-round, groups of six to eight individuals, ranging with problems from autism spectrum disorder, drug abuse, or depression, backpack through the desert or ski tour the Wasatch, says Joe Nagle, Adventure Facilliatation Trainer for Aspiro.

“Doing things that are difficult, especially things that you didn’t know you could do before, translates really easily to whatever you are coping with at home. We found a model that works with a broad range of students,” he says.

They grow in identity coherence, or the ability to know themselves and take pride in who they are, as well as gaining effective coping mechanisms. Pushing limits outdoors can be scary, but believing in yourself and then doing it makes you confident in your abilities.

Nagle knows that, like PTSD recovery, these changes are only possible through the combination of nature and therapy, but there’s no denying that nature is a necessary ingredient.

A PRESCRIPTION FOR NATURE

Stories abound about people stepping into nature to find healing. Most revelations recorded in scriptures happened outdoors just think of Moses on Mount Sinai, Jesus Christ in the wilderness, or Muhammad in the Cave of Hira. In ancient literature like The Odyssey, nature is part of the healing, says Stacy Bare, director of Sierra Club Outdoors.

Bare has been working with researchers, mental and public health professionals, and outdoor advocacy groups to bring the conversation back to the outdoors.

“People see, finally, that this is another way for preventative as well as treatable care,” Bare says. “We need to view our public lands as a public health care system. The benefits of getting outside are incredibly real.”

Park prescription programs are starting to emerge, such as the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Outdoors Rx program, which prescribed active outdoor activity for children and adults suffering with obesity and high blood pressure. Bare himself found healing through climbing, hiking, and skiing after serving in the military for five years.

Last year, Bare, Strayer, and others met at the White House to propose a plan to get people off drugs and into nature. Yes therapy and medication are important, but there is a natural healing element that happens when you smell a ponderosa pine or touch a trickling mountain stream.

After millennia of proof from poetry to films, the data is catching up. Nature changes us. And if you don’t believe it, take the advice from Henry David Thoreau. You’ll walk away feeling taller than the trees.

Photos courtesy of Aspiro Adventures