When driving down I-215, heading towards Little Cottonwood Canyon to flail on something presumably moderate, I am always drawn towards this pile of rock right before the entrance of Parley’s Canyon. Its painted ramp is somewhat reminiscent of a child’s vomit right after he ate too many Skittles, and it curiously draws your gaze like a moth to a flame.

Suicide Rock rises above the old, dried-up Parley’s Reservoir, a site that used to be shrouded in legend. Early 1900s photos and drawings depict the rock as magnificent and proud. According to a plaque nearby, the name “Suicide Rock” originates from a tragic story of a Native American woman leaping to her death after the sudden passing of her heroic husband.

However, its once legendary status is now reduced to nothing but a place where folks go to “Chute the Tube,” or to deface its once clean, quartzite, features. Defacing the natural beauty of a feature like that is, in my opinion (and frankly many other’s opinions), wrong. Even if that thing may be a pile of sorts and a new-age “icon”, it does not deserve to be reduced to an amalgamation of dried spray paint surrounded by a nest of empty beer cans.

Driving past Suicide Rock, I would always wonder how many other places in the Wasatch are faced with such abomination. I mean, I spend a lot of time in the Wasatch canyons and I have surprisingly never seen even a smidge of some delinquent’s self-proclaimed “pictograph” on any rock. There could be several reasons for this, maybe I don’t get out as much as I think or maybe I am just not looking hard enough. However, a huge part of it could be due to Peter Lenz and the Wasatch Graffiti busters.

Peter Lenz is a retired ER doctor and a climber. He resides near the base of Big Cottonwood Canyon and is in his late 60s. Originally from Rhode Island, he was subverted into a life of climbing when he learned about the first American ascent of Mt. Everest in 1963. In the mid 60s, his father moved his family to Seattle where he was fortunate enough to summit Mt. Rainier with prominent alpinist, the late John Harlin. Lynz accomplished this feat when he was just 13 years old.

Unfortunately, Lenz was forced to move back to Rhode Island the year after, and was unable to do much of any climbing. It wasn’t until he returned to Seattle to attend the University of Washington that he was really able to get after it. Peter spent most of his time climbing alpine routes in the Cascade range, while also venturing up on several tips to the Hayes Range in Alaska.

Unfortunately, Lenz was forced to move back to Rhode Island the year after, and was unable to do much of any climbing. It wasn’t until he returned to Seattle to attend the University of Washington that he was really able to get after it. Peter spent most of his time climbing alpine routes in the Cascade range, while also venturing up on several tips to the Hayes Range in Alaska.

After graduating from University of Washington School of Medicine, Peter entered into his residency years to further his education and practice on internal medicine. This ultimately landed him a position as a ER doctor at the LDS Hospital in downtown Salt Lake City. Lenz’s arrival to the valley allowed him to get after it more than he could up in the PNW. The easy access to the canyons and working relatively few hours a week afforded him ample opportunities. But not as much as we would have liked.

After his retirement in 2018, Peter felt a void. He described the dream he had all of his career of being able to quit someday so that he could really pursue the things that he loves. This includes climbing, skiing, hiking and pursuing his talent at the guitar. However, when his dream came to fruition, he ultimately felt empty.

“I went from being this accomplished, respected doc who was doing really important work and, you know, in a way, that all of it was true. That really was what was going on,” Peter told me. “And now I was, I was nothing.”

However, that would change when Peter found a new purpose and a new direction. This was graffiti. And the art of busting it.

In the same year that Peter retired, the Wasatch was experiencing a string of graffiti tags on prominent places in the canyons. One of the most heavily hit areas was the Temple Quarry Trail and the Gate Boulders in Little Cottonwood Canyon. It got so bad that the Salt Lake Climbers Alliance (SLCA), who had been previously self-tasked with removal of the graffiti, just couldn’t keep up.

As a result, the City of Sandy decided to hold a “Graffiti Conference,” in hopes that someone would be able to get rid of the graffiti and the subsequent vandals that had plagued the community. Peter, and scores of other folks, were in attendance at this conference in hopes that a plan could be established. However, it seemed to Peter and a few others that something was not going to happen soon enough.

It wasn’t until the conference came to a close, that Peter found a few other individuals that felt the same sense of urgency as himself. These individuals were Scott Whipperman and Bob Walker, and the three ultimately decided that they would tackle the problem head-on.

The Wasatch Graffiti Busters is a non-profit organization that was ultimately founded by the three men after this fateful day. They were successfully able to remove the graffiti from the two heavily hit areas by a simplistic yet fascinating process that Bob Walker had learned through his time removing graffiti in the SLCA.

“Bob Walker, who had experience with the SLCA, taught us the best way to remove graffiti: apply Elephant Snot with a roller or brush, wait 20-30 minutes depending on the temperature, scrub with a brush, and wash it off with water,” Peter explained. “Bob also suggested using portable power washers from Sun Joe, which are small enough to fit in a large backpack. We still use them to some extent.”

This portability allowed the team of three men, and several other volunteers, to reach even the most obscure places in the Wasatch. Peter reminisced of a time where they were able to remove graffiti from all the way up at “The Pawn” in Little Cottonwood Canyon. And if anyone knows that approach, they know it is an absolute pain to haul a rack and a rope up. Let alone several large containers of water and portable power washers.

Due to their efficiency, the Wasatch Graffiti Busters have become the “go-to” team for both the National Forest Service and the Unified Police Department for canyon graffiti removal. The group became so effective they are seeing a decrease in activity. The Wasatch is no longer experiencing graffiti issues as it once did. Perhaps the vandals have taken up climbing and adopted similar values, or maybe defacing rocks has simply fallen out of vogue. It’s also possible that the Busters’ relentless dedication to removing graffiti has caused these vandals to straight up quit.

However, there are a few places in the Wasatch that still get the occasional tag or repeat graffiti art. I was fortunate enough to have Peter show me some of these degenerate places.

On the morning of July 17, the day of this article’s deadline (sorry Maitane), Peter and I loaded up in his white 4-runner and set off for Ledgemere Campground in Big Cottonwood Canyon. As we pulled-off the side of the road, Peter exclaimed “See that gray spot right there? Yeah that’s some remnant of graffiti that we did a poor job removing.”

I stared at the brown quartzite wall, failing to see what he had pointed out.

“What? Where?” I replied.

“I’ll show you.”

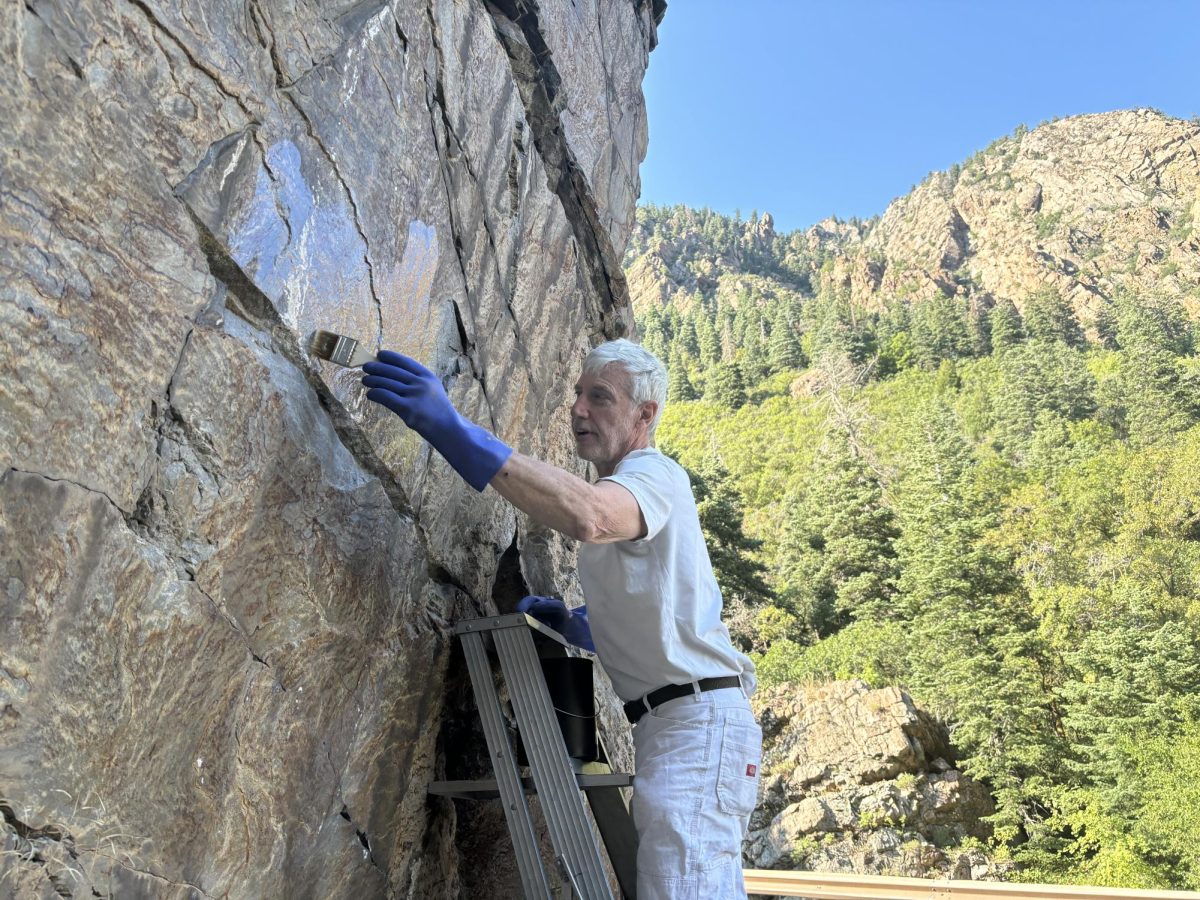

So we got out of the car and unloaded his graffiti removing gear from the car. Peter, dressed in his white painters outfit, propped up a ladder next to where the supposed “poor job of removal” had occurred. He pointed it out once again and explained that it can be quite tricky to see to the untrained eye. In my mind, not being able to notice it was “super good enough.”

I quickly found this naive way of thinking to be distraught. It wasn’t good enough for Peter because it was still noticeable to him and thus still there. Thus still defacing the rock even if it wasn’t noticeable to the vast majority of people.

Peter then began to apply Bob’s miracle Elephant Snot to the affected area, and while the solvent sat, we went across the street to the Ledgemere Cave. A place that has been repeatedly hit by graffiti, and one of the Graffiti Busters’ most frequented areas. Lenz led the way as we crouched into the confined opening until we were able to stand up in the cool and damp cave. We wandered to the back where he pointed out the large pieces of graffiti that had sprung up recently. He also explained the difficulties of dealing with it in such a confined area.

“It’s a particular problem here because the space is so narrow that using Elephant Snot coats you in it. Spraying paint creates a huge fire hazard in such a confined area, and the wet walls prevent it from sticking well. So, we’ve decided to just paint over the graffiti, as it seems like the only safe solution.”

When we exited the cave we walked around Ledgemere looking for more. We ultimately found nothing and eventually wandered back over to the wall where the solvent was still sitting. Peter then got his power washer out and blasted the wall. Once he was done, Lenz brought me back over to show me what had been done. The remnants were now gone and the rock was now back to its natural state. It was no longer defaced.

After this, I asked Peter about what he thought about Suicide Rock, the place that had sparked my inspiration for this story. He said that him and the Graffiti Busters have been wanting to do something about that for years. However, he added that tackling something that big would be quite time and cost intensive.

“There’s almost a centimeter of paint on that thing. We also couldn’t use the conventional Elephant Snot method that we use today and would have to probably chisel it off. It would take at least two summers to completely rid it of all its paint. I would really like to do it. That place should really be a park.”

Today, the Wasatch Graffiti Busters consists of four prominent members. The aforementioned Scott Whipperman is the president of the organization and Peter Lenz is the Treasurer. Mary Young is the 86 year old secretary who still manages to get after it and helps with raising money, paperwork and PR. Brent Hamblin is the newes, and youngest, member of the team and helps out when he can.

The team is facing an issue of their aging staff, however. Peter tells me that the climbing community has been great about helping out when they really need volunteers, but that the core of the organization is aging. He says that he simply can’t carry five gallon jugs up steep boulder fields like he used to.

The SLCA and the Wasatch Mountain Club are both organizations that have been historically tasked with the removal of graffiti long before the Wasatch Graffiti Busters even existed. Peter emphasized their particular important role in this area and that their contributions are not to be missed. Lenz nods that these organizations are likely going to pick back up when the Wasatch Graffiti Busters go belly up, because “we are simply getting too old!”

The Wasatch Graffiti Busters are looking for younger members to help keep this fantastic organization alive. If sanctifying the Wasatch is something that interests you, the reader, please don’t hesitate to send a message to: Wasatch Graffiti Busters, PO Box 56150, Cottonwood Heights, UT 84121. Or send a message to Save Our Canyons online describing your interest.

If you see graffiti in the canyons, make sure to contact the U.S. Forest Service or the Unified Police Department. It will be rest assured that Peter Lenz and the Wasatch Graffiti Busters will get it taken care of, even if they are a little old.