Amidst this year’s summer films, few compelled and surprised me quite like Jurassic Park Rebirth. When first announced I was ready to complain about yet another re-boot. However, the first trailer promised more fun filled dinosaur drama, even if it did turn out to be just an entertaining cash grab like Jurassic Park 3–one of my guilty pleasures.

However, what surprised me more about Rebirth’s marketing campaign was the sense of déjà vu it gave me. The language, the drama, and the “new era of science” shot me back to earlier this year. I saw the same sensationalism, sugar-coating genetic and environmental science, that happened when a real company went viral for their so-called de-extinct dire wolves.

Wolves of De-extinction Street

Dire wolves were a canine species that lived between about 50,000 and 13,000 years ago, and were comparable in size to modern gray wolves. According to a scientific article published in the journal Nature, dire wolves formed a distinct genetic lineage and show no evidence of interbreeding with gray wolves. Grey wolves themselves diverged from the dire wolf lineage around 5 million years ago (Perri et al, 2021).

For environmental scientists, the short story is that Colossal BioScience did not de-extinct dire wolves, and dire wolves are not the species to focus on in conservation efforts. Though there are only small percentages of the grey wolf and dire wolf genome that differs, those small percentages make big differences. 1% of a genome can have around 10 million DNA base pairs, each critical for an organism’s unique species identity. In Colossal BioScience’s wolves, they altered only 20 base pairs. Additionally, ancient dire wolves went extinct, not only due to competition with humans, but to a naturally warming climate. If true dire wolves dropped into an environment that is continuing to warm and lacks earlier amounts of large prey species, there is no way they would flourish, much less help the environment.

That said, Colossal BioScience has done an incredible scientific feat. They have created some of the first genetically altered, viable clones, which has huge implications for conservation efforts focused on improving biodiversity and strengthening endangered species’ population health. However, explaining that can be hard and—especially for an unfamiliar audience—even harder to market. More attention and more investors can come from simply saying “we have done the incredible and created dire wolves.”

For a company or scientific innovator, the work can’t be done without funding. This often forces science to also become profitable. So, what sells? A famous author posed with one of his “de-extinct” characters. A science-fiction franchise getting its third wind. Excitement, awe, and adrenaline from any source, no matter if it is accurate or not.

But what if we were to use those sellable traits to promote accuracy in sharing innovations in environmental science and thoughtful discussions into their applications? In 1990, Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park was trying to do just that.

The Incredible Park-Razing Dinos

It was fortuitous, on the coattails of the viral wolves and with first Rebirth trailers arriving, that my brother picked the original Jurassic Park novel for our book club.

Like the films, Jurassic Park has a decidedly gory hook. However, as a novel it has the time and space to delve deeper into themes of hubris and corruption, which it takes advantage of in an easy-to-follow narrative style. The book uses genetic power to explore dangers of picking-and-choosing science that fits your brand, prioritizing profit over lives, and assuming scientific progress equals God-like control.

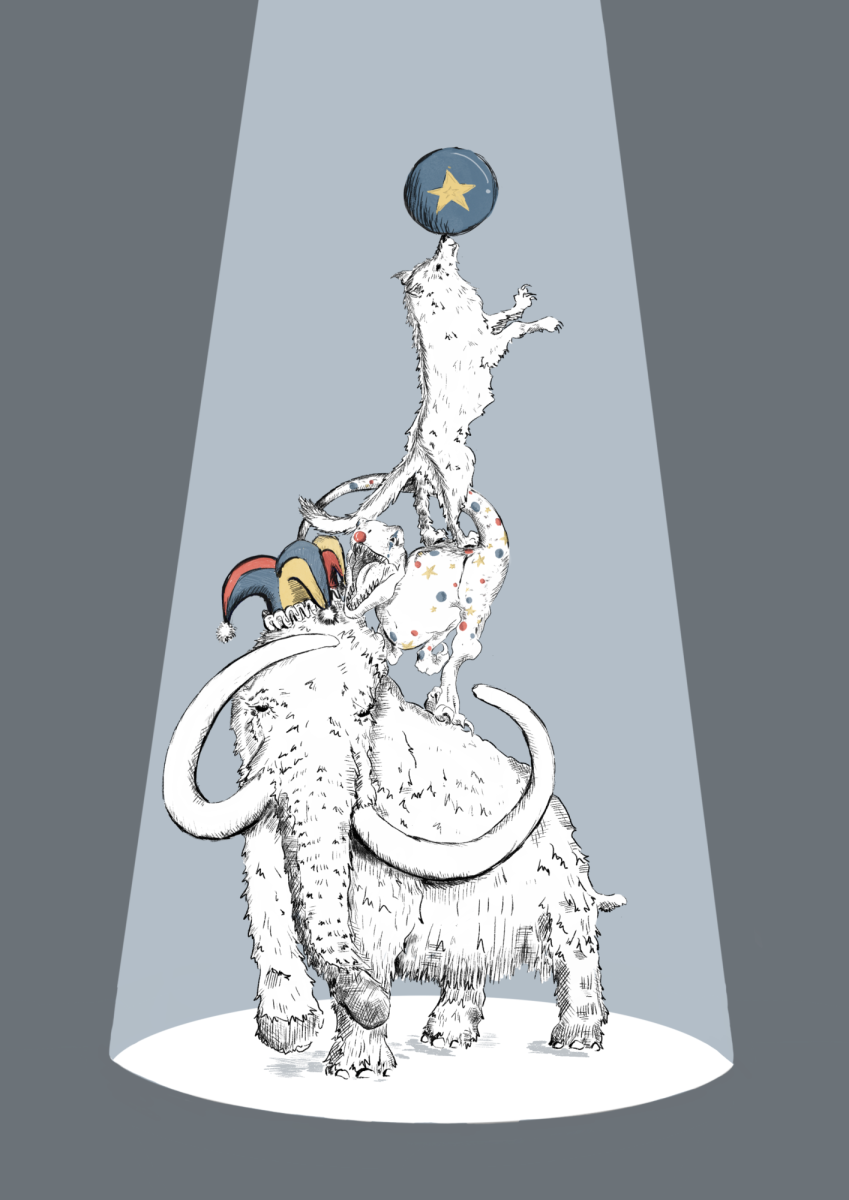

The novel shows these themes primarily through the novel’s antagonist John Hammond. Like Colossal BioScience’s marketing, Hammond started off promoting a single creature that showed genetic power’s potential. In his case, a miniature elephant. Yet in securing investors, Hammond glossed over the elephant’s true identity—an identity impressive in its own right. The novel writes, “Hammond was starting a genetics company, but the tiny elephant hadn’t been made by any genetic procedure; Atherton had simply taken a dwarf-elephant embryo and raised it in an artificial womb with hormonal modifications. That itself was quite an achievement, but nothing like what Hammond hinted had been done.”

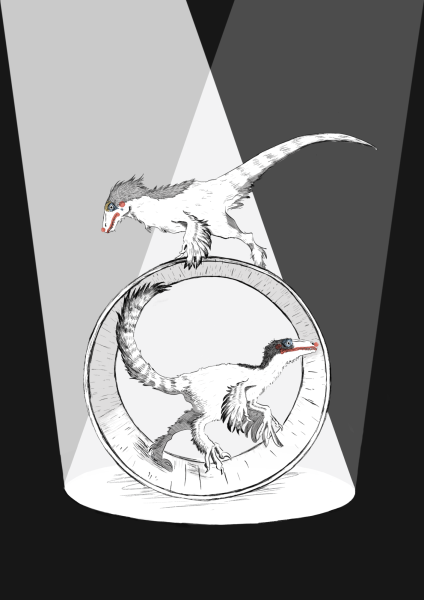

Later, after building Jurassic Park, Hammond still only focuses on what would make the park appealing: the circus-like, theme park traits instead of a zoo full of unfamiliar, unpredictable animals. He even ignores the safeguards real zoos are willing to enact when human lives are at risk. Another character tells Hammond, “It’s your park, Mr. Hammond. You didn’t want anybody to hurt your precious dinosaurs. Well, now you’ve got a rex in with the sauropods and there’s not a damned thing you can do about it.” Hammond’s ideas are made even clearer by the antithetical, equally satirical extreme of Ian Malcolm, who staunchly repeats that humanity has little knowledge and less control of the natural world, and that life always “uh, finds a way.” Even Alan Grant has a moment realizing his own hubris when, amidst the park he realizes the inherent limitations of paleontology when compared with a living dinosaur standing in front of you.

Now on its seventh feature film, the Jurassic Park franchise has seen cycles of heavy-hitters and mediocre cash grabs. While Crichton’s theme of human hubris has been an undercurrent in various forms, the franchise has still fallen prey to other dangers the book presents.

Behind the Curtain

All the nuance in Crichton’s nearly 500-page work is just the tip of the environmental scientific innovation iceberg. It makes it harder then to distill it further into a two-hour film. When condensing the narrative science to a general public (in which film already tends to sell better than books) some things have to be left out. And with humans’ tendency towards the fantastical, the focus tends to shift towards what people want to see, not what they need to hear. As much as I personally enjoy discussing complex environmental science, I would be remiss in saying that I don’t enjoy watching rampaging dinosaurs. Like Hammond focusing on the theme park side of his island, the Jurassic Park films focus on the gory hook, not so much the message.

So where does that leave our scientists? How can science communication learn from Jurassic Park’s self-fulfilling prophecy? Jurassic World Rebirth film has, in some ways, done that. Not necessarily a fan favorite, the film changes its story to fit into a place similar to where the audience is, not where the audience wants to be. It presents its drama in a world where dinosaurs are not new. Yet, with a cast of new dinosaur freaks it still creates beautiful visions, and uses its own Malcolm-like character to deliver the straightforward themes: how the world will continue after us, the inequalities born from greedy companies, and how to navigate human-wildlife conflicts and wildlife management ethics.

How would the dialogue would have been if when G.R.R. Martin was promoting Colossal BioScience’s “dire wolves,” they also asked him to promote their successful red wolf clone? If the company used the talking point to show their bone-a-fide member of a currently endangered species? If, like Jonathan Bailey’s character, they used the de-extinct wonders to give a nudge towards real life injustices? Or to take it further, what if a Jurassic Park-like film took inspiration for their big-screen mutants from Tasmanian devils, whose populations are under attack from a contagious face cancer (Woods et al, 2018). (It is unlikely the cancer can affect any other species. Though it is no danger to us, it still deserves our attention).

There will always be a divide between long- and short-form media and compromises between audience engagement and paying for the finished work. But in my opinion, with care, accuracy, and creativity, more marketable film, literature, and social media can open the door for deeper, more nuanced conversations around outdoor scientific innovations. Just like Jurassic Park and Jurassic World Rebirth did for me.

La Fin.

References

Crichton, M. (1990). Jurassic Park.

Edwards, G. (Director). (2025). Jurassic World Rebirth [Film]. Universal Studios.

Perri, A. R., Mitchell, K. J., Mouton, A., Álvarez-Carretero, S., Hulme-Beaman, A., Haile, J., … & Frantz, L. A. (2021). Dire wolves were the last of an ancient New World canid lineage. Nature, 591(7848), 87-91.

Woods, G. M., Fox, S., Flies, A. S., Tovar, C. D., Jones, M., Hamede, R., … & Bettiol, S. S. (2018). Two decades of the impact of Tasmanian devil facial tumor disease. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 58(6), 1043-1054.