Bolting Wars: Trad v. Sport Climbing

You are on Belay

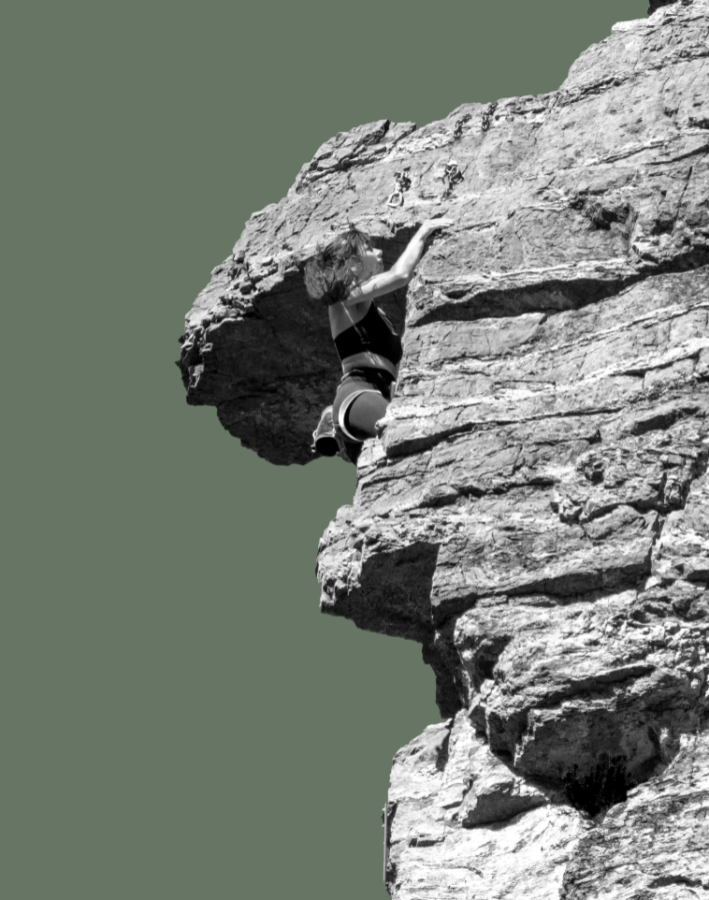

This article is intended for new climbers and boulder rats. Here, I will introduce you to a conversation that has been going on in the climbing community for generations. To bolt or not to bolt? Climbing practices surrounding accessibility, safety, and traditionalism guide many first ascensionists when establishing a new route. What is the balance we should strike between risk and risk prevention? Which variables might call for bolts and which do not? Similar to conversations surrounding National Park developments, balancing a natural environment with anthropogenic forces will always be a complicated issue.

So When Did Bolting Start?

The late ’50s saw some of the earliest uses of expansion bolts in climbing. Warren Harding, Wayne Merry, and George Whitmore would use bolts to obtain the first ascent of the iconic Nose route in Yosemite National Park. With the inclusion of these technologies, harder and harder climbs began to become possibilities for aspiring ascensionists. This opening of Pandora’s box allowed climbers to seek out challenges far beyond what previous generations would have been able to. Inevitably, this would lead to the drilling of bolts in otherwise unclimbable areas of the world.

In 1976, two such climbers, Stéphane Troussier and Christian Guyomar, rappelled down the blank walls of the Verdon Gorge in France, the earliest known sport area in the world. Following closely behind, and inspired by these French climbers, Alan Watts and other frequenters of Smith Rock State Park in the United States began establishing some of the most difficult sport routes of their era. It’s inarguable that bolting routes has completely reshaped the sport of climbing for the better. The argument around bolting is instead about whether EVERYTHING should be bolted, or if we should instead set clear boundaries for when bolts should be avoided.

Why or Why Not?

The truth is that there is no black or white answer to the question of whether or not to place bolts on a climb. If there is a long runout “sea of granite” slab section on a climb, then it might be nice to have a bolt or two to improve safety. If there are cracks splintering along the wall, then bolts are likely unnecessary.

Even in these clearer examples, some will argue that ensuring access to safe climbing is always the most important goal. Other contrarians will say that risking whippers is an essential part of the climbing experience. If we really wanted to leave no trace, shouldn’t we all just free-solo everything, à la Alex Honnold? To improve upon accessibility and safety, shouldn’t we physically alter the rock to create better holds, or place bolts every three feet? Obviously, there needs to be a middle-ground, but striking that balance has proven difficult for this intergenerational community.

Trad Climbing

Rock climbing, as an activity, was first undertaken using practices that were more akin to free-soloing than modern trad climbing. It wasn’t until the early 1900s that pitons and carabiners were first introduced as additional points of protection for climbers. Prior to the introduction of these technologies, climbers led routes with only a rope tied around their waists. These protections would be one of the first step towards safety taking precedence over a rock’s natural quality.

Within modern terms, trad climbing includes the use of both passive placements, like nuts and hexes, as well as spring-loaded camming devices. Nuts were first introduced in the late 1950s, while cams wouldn’t come into play until the 1970s. This removable protection also includes natural forms of protection, like wrapping a sling around a tree or a chockstone. Even the most experienced climbers are likely to have pieces of gear pull out of the wall every now and then, generating a much bigger “whip” than almost any sport climb would allow.

Sport Climbing

Within our modern age, sport climbing is by far the more popular and accessible form of climbing. It can be done indoors and outdoors, and monetarily speaking, requires very little buy-in. Sport routes are defined by the metal bolts and hangers that are drilled into the wall, tracing along a route. These hangers allow for a relatively quick point of attachment for the climbers, via quickdraws. Bolts are intended to stay in place for years and are only replaced when the wear-and-tear becomes noticeable or placements are questionable. Because of this style of route-setting, protection is able to be spaced out in ways that can improve upon one’s route-finding ability and their ability to take risks. With these predetermined clips, falling becomes an almost controlled experience. The crux, which is the hardest part of the climb, is able to be well-protected, further decreasing the dangers.

The drawbacks for sport climbing are a bit more abstract than for trad. Some will argue that standardizing a route detracts from the climbing experience itself. In this way, bolts are seen as an uninspired alternative to achieving an ascent where a route could otherwise be protected with traditional gear through moderate run-outs. Leave-no-trace principles also are overlooked when bolting routes, further skewing the line between connection and dominion. Finally, bolt placements often rely on the decision-making of a single individual, while trad placements are reliant on the active climber’s judgment. While seemingly benign, climbing styles and general physiology can have huge implications on how accessible a given bolt actually is.

To Chop or Not to Chop

These contrasts between risk and access are where the bulk of the “bolting wars” originate. Are safety and accessibility more important than the natural quality of the rock? Do you have to earn your way into certain climbing areas by way of risk, hard work, and a $1,000+ rack of gear? Is this simply an unavoidable clash of ideologies?

The reality is that bolting ethics are as much about culture and dominion as they are about generating any definitive answers. These debates are more suited for those seeking first ascents rather than those following already established trails. Given the fact that most of us will never take part in a first ascent, our primary focus should instead be on staying educated rather than opinionated. So put down the drill or bolt cutters and start exploring the local climbing ethics of your area.