Climate Change Comes for Utah

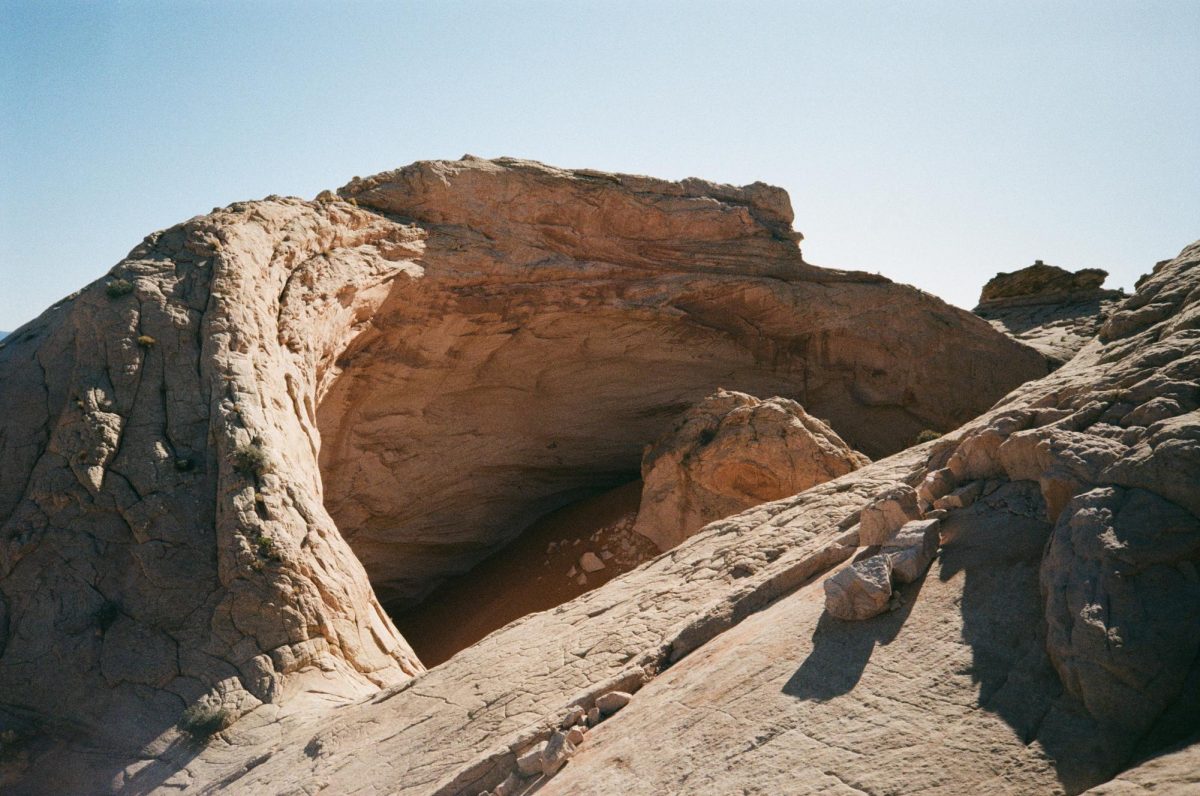

Photo by Kiffer Creveling

December 31, 2019

Climate change is a hard topic to wrap your head around. All data and detailed predictive models scream that things are not going well. Yet, it’s almost impossible to directly experience the effects of a few percentage changes in the “average” seasonal temperature that has taken place over several years. In the Mountain West, weather changes by the hour and our body’s sensory systems are focused on the here and now, not what the temperature felt like on this same day in the calendar for the past 10 years. Even on a yearly basis, it’s hard to see a trend unless you look very closely. But if global emissions continue at their current rate, or evenly decrease slightly in the near future, someday the bill will come due.

Although the crisis is dear, the state government of Utah has thus far failed to act, and it seems doubtful that any meaningful action is on the horizon. If you need any proof of this, just put down this magazine and take a look outside. Can you see downtown? How about the Oquirrh mountains? Chances are that by the time this issue comes out, the inversion season will be in full swing once again. Remember, the poisons in the air are only visible because of the special combination of cold weather and snow on the ground. The rest of the year, those same chemicals are still escaping into the atmosphere relatively unnoticed.

Although these toxins may escape unnoticed in the summertime, their consequences are far from invisible. A feature study published on Vox.com in July 2019 used advanced climate models to predict changes to 30-year average temperatures in major cities across the United States. Their estimates show that by 2050, the 30-year average in Salt Lake City could be as much as 5.1 °F warmer when compared to 2000, elevating the average winter low from 23.9 °F to 29.0 °F. While this will still be cold enough for water vapor to freeze into snow, the consequences are complex. In general, warmer air is capable of carrying more water than colder air, which leads to more precipitation. An increase in temperatures may actually lead to more rain and snowfall in the mountains. The warmer temperatures, however, will likely lengthen the duration of “shoulder” seasons, and shorten the amount of time that precipitation lands in the mountains as snow rather than rain.

A joint research project from the University of Washington and Ouranos Inc., a Canadian climate consultant group, modeled the possible outcomes from various different changes to overall temperature and precipitation in the northern hemisphere. Their analysis showed that the metrics most sensitive to these changes were snow cover duration — a measurement of the length of time where a significant amount of snow is on the ground — and snow water equivalent — a standardized measure of snowfall that accounts for the density of snow along with the depth of a snowfall. Based on their models, duration and magnitude of snowfall in coastal regions such as the Cascades would be highly affected by changes to temperature and precipitation due to their proximity to the ocean. Continental mountain climates such as Utah and Colorado would experience a more complex scenario where the duration of snowfall would likely decrease while the amount of snow over a given season would likely remain the same or even increase in some cases. To some Utah residents, a shorter winter may be a welcome change, but to others, it could put them out of a job.

Protect Out Winters, a nonprofit organization founded by professional snowboarder Jeremy Jones, has done some deep dives to quantify the economic impact of the ski industry in the United States. In a 2012 report, they found that the ski industry in Utah alone generated $425 million in labor income and a total of $744 million added to the local economy. In part of their report, they used data from high and low snow years to estimate the economic damage of shortened winter. In Utah, they found that lower snow years had 14% fewer ski days, $66 million less economic value generated and over 1,000 few jobs. These losses are not limited to the mega-resort conglomerates, but they affect all aspects of the local economy from lodging and dining to equipment shops and taxi drivers.

One aspect of the Utah ski scene that wasn’t directly addressed by many of the reports by POW is the vibrant culture of backcountry skiing in the Wasatch and beyond. To gain some insight into how all these potential changes to the local climate could affect the recreation of those that forgo the lift lines and reliably groomed runs of the resorts, I reached out to the off-piste experts at the Utah Avalanche Center. Their director, Mark Staples got in touch with me and explained that backcountry snow pack stability is so highly dependent on hourly and daily changes in weather, that making any long-term predictions about the quality and relative safety of backcountry skiing was virtually impossible. He did offer an anecdotal observation that mid-winter rain at higher elevations seems to have become slightly more common, and may continue to do so if winter temperatures increase significantly. Rain, for those who are unfamiliar, is not known as a key ingredient to the high-quality powder skiing that Utah is known for.

Given that oil weighs more than water both on the periodic table, and in the mind of state legislators, it is easy to accept that the future of Utah’s snow and ski industry looks bleak, but the ski resorts have decided to fight back. Since 2012, the National Ski Areas Association has issued a yearly climate challenge, where ski resorts voluntarily set goals to reduce their direct and indirect contributions to greenhouse gas emissions. In 2019, 26 resorts across the nation, including Alta, Deer Valley, Solitude and Snowbird have accepted the challenge to reduce or at the least maintain their own emissions. Alta Ski Area has embraced the challenge by forming its own environmental center which focuses on implementing sustainability into ski area operations through a multipronged approach that focuses on conserving and bettering the land and reducing the ski area’s overall environmental impact. The director of the Environmental Center, Beth Yetter, described that Alta Ski Area has worked towards its goal of a 20% reduction from 2010-11 greenhouse gas emission levels. Efforts to reach this goal include but are not limited to upgrading the efficiency of lighting, appliances and snowmaking equipment throughout the resort, the construction of a LEED-certified skier services building and the installation of three solar panel arrays. In addition, Alta Ski Area has implemented a revegetation, reforestation and restoration program which resulted in planting over 4500 plants and 1400 trees in summer 2019 alone. Plants and trees used for revegetation and restoration efforts within the ski area are grown from native seed that is collected from the ski area every summer.

Clearly the resorts are aware of the potential harm to their bottom line, should the trends of climate change continue while they are contributing to emission reduction, they are also preparing for a possible new reality. The recent growth of the Icon and Epic pass systems, which allow pass holders to access a wide variety or resorts across the world, can be seen as a hedge against poor winters for a resort. By joining the profit-sharing system of a multi-resort pass, individual resorts are able to spread the risk of a low-snow season across the globe. This strategy, however, produces a somewhat of a Catch-22. By providing economic incentives for skiers to travel to better snow, they will inherently encourage more emissions through road trips or long-haul international flights that might not have otherwise be generated.

Such is the conundrum of climate change. Must the all-day tram laps stop? Should we shut off our electricity, turn off the gas that heats our homes, bundle up for the winter and eschew the recreation that makes the reality of the 9 to 5 grind bearable? Must we park the cars, never to see the far reaches of a desert wash again? When looking down the barrel of a gun that could deliver the most devastating shot to humankind in its history, particularly to those who don’t sit safely at 4,500 feet above a rising sea level, what is the responsible choice to make? Some might say that many of the activities we all love to enjoy are wasteful and unethical in the face of climate change. It is hard to argue with them, but then again, it is difficult to build the coalition necessary to steer the battleship that is global climate by taking away the things that bring each of us solace. It is easy to look on with cynicism as the companies sitting atop $12 billion in economic value cloak themselves in the language of climate activism while seeking to secure their bottom line, but before you judge them too harshly, ask yourself what you are doing? Are you making the seemingly small changes that help build to a more sustainable future by reducing household waste and limiting unnecessary time in the car? Are you using your vote to demand that those that seek to externalize the costs of their contribution to the climate crisis are made to pay their fair share? If you can answer yes, go forth and ski easy my friend. If not, the next time you ride the lift, make a plan of action because otherwise, the snow may not last long.