The Lawsuit Challenging Southern Utah’s Wilderness

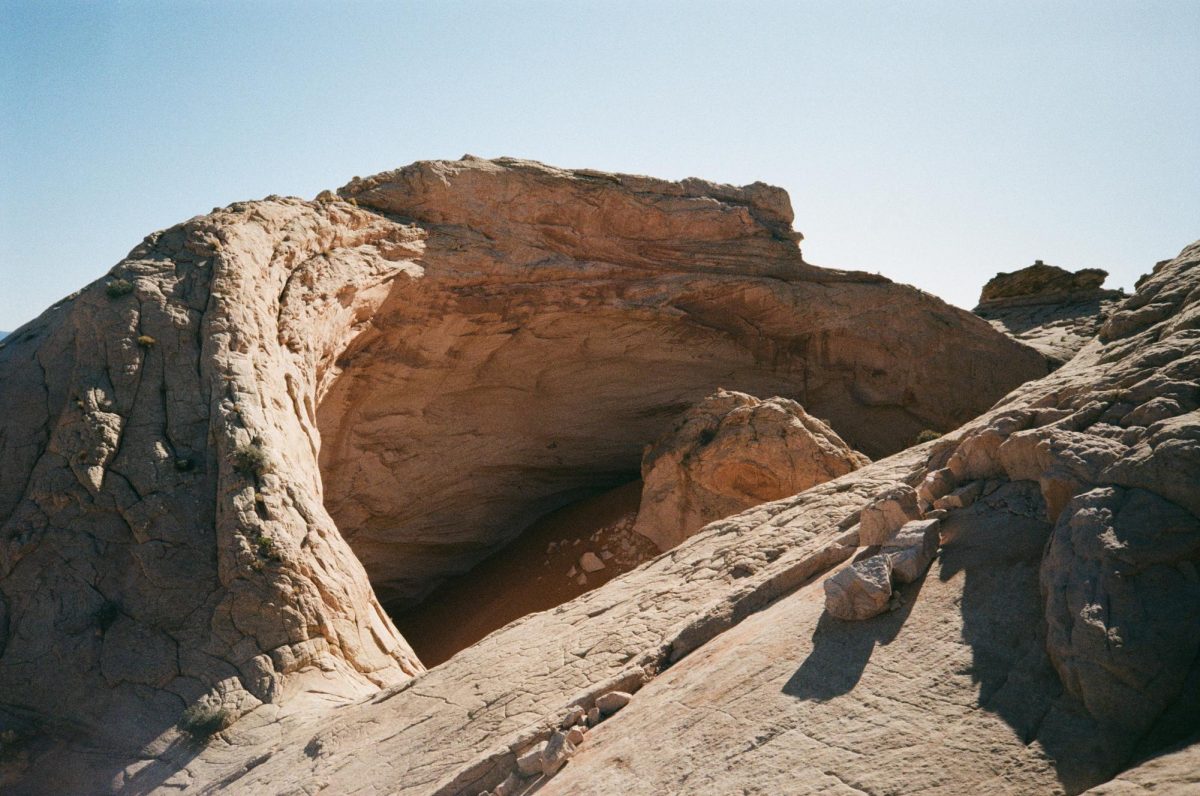

Photos by Kiffer Creveling

October 29, 2019

A federal lawsuit filed this summer against the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is threatening the recent wilderness designations in southern Utah’s San Rafael Swell.

In March 2019, President Trump signed the John Dingell Conservation Management and Recreation Act, a sweeping bill that, among other things, expanded eight national parks and designated new wilderness areas across the Western US. An uncharacteristic move from an administration not known for its conservationist policies, the Dingell Act is the largest expansion of public lands in a decade.

Included in the bill’s 170 provisions is the Emery County Public Lands Management Plan, which sets aside over 700,000 acres of wilderness in southern Utah. Areas like Muddy Creek, Big Wild Horse Mesa and Red’s Canyon are now wilderness, the government’s most protected classification.

The Dingell Act was a rare glimpse of true bipartisanship, passing 92-8 in the Senate and boasting a diverse list of cosponsors. Praised by the likes of Dianne Fienstien, Mitt Romney, and even Mitch McConnell, the expansion comes at a time when, according to a 2018 Gallup poll, public support for land conservation is high.

But the Dingell act could not escape controversy. In July, Utah residents Rainer Huck and John Anderson took aim at the state’s wilderness, filing a civil complaint against BLM.

“The BLM is systematically discriminating against people who are handicapped or disabled,”Huck said, the driving force behind the current litigation. The former Salt Lake City Mayoral candidate claims that the decades-old Wilderness Act has been “mutated” by the environmental community.

Passed in 1964, the Wilderness Act was designed to preserve the country’s most remote and undeveloped land, barring all motorized travel. “When they ban vehicles, they ban people,” Huck said, who at 73 has physical limitations that prevent him from non-motorized recreation on public lands. The complaint hinges on allegations that the Dingell Act violates the first and fifth amendments by making concessions to so-called “earth religionists,” and denying off-roaders due process.

As the former director of the Utah Shared Access Alliance (USALL), a non-profit focused on advocating for motorized travel on public lands, this isn’t Huck’s first time in the courthouse. Over the past 20 years USALL has been involved in 18 lawsuits, a number of them challenging wilderness designations and land-use restrictions.

“We certainly disagree with many of the positions USALL has taken but don’t dispute their right to have their voice heard,” said Steve Bloch, Legal Director for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance (SUWA). One of Utah’s leading voices for wilderness designations and land preservation, SUWA has opposed USALL in numerous appeals and lawsuits. Bloch stresses that Huck and other off-roading advocates only represent one of the many opinions that state and federal land managers take into consideration.

“Admittedly certain uses are not allowed in wilderness areas but that’s really no different than how agency decisions to allow coal mining on public lands can exclude other uses,” Bloch said, adding that the passage of the Dingell Act still leaves thousands of dirt roads and trails for motorized use on Utah’s public lands.

But for Huck, this argument is proof of what he deems government overreach and discrimination. “I don’t think the BLM and SUWA should be the arbiter of what’s enough access,” he said. “They’re like religious extremists, they have their beliefs and they don’t care who they hurt.”

The wilderness areas in question are rich in human history. The San Rafael Swell was home to indigenous cultures like the Fremont, Paiute and Ute, with ancient petroglyphs and pictographs scattered throughout the rugged landscape. More recently, the region was home to large scale uranium mining and ranching, with hundreds of miles of dirt roads winding through steep canyon walls and eerie ghost towns.

Huck argues that the existing roads and extensive human use disqualify the region as wilderness. “That whole place was crawling with tens of thousands of miners with heavy equipment…it’s not pristine.” But proponents of the new wilderness designations argue that the area’s indigenous history and unique landscape requires stringent protection.

When asked about his next step, Huck said he’s still waiting to hear from the BLM. “Ideally they’re going to say ‘oh yeah he’s right, we can’t fight this,’” he laughed, speaking over the phone from his camper in southern Colorado. But even he admits that this is his last gasp. “I’ve been beating my head on this for a long time.”

The future of Huck’s lawsuit is uncertain at best. If past rulings offer any indication of what’s next, the case will likely be thrown out. “Courts have rejected these arguments before, I don’t expect a different outcome this time around,” Bloch said.

As the public lands debate continues to rage across Utah, Bloch stresses the importance of compromise. “It’s not a question about all or nothing but about striking a balance between uses,” he said. “Part of that balance is preserving deserving landscapes for current and future generations.”