Making the Grades

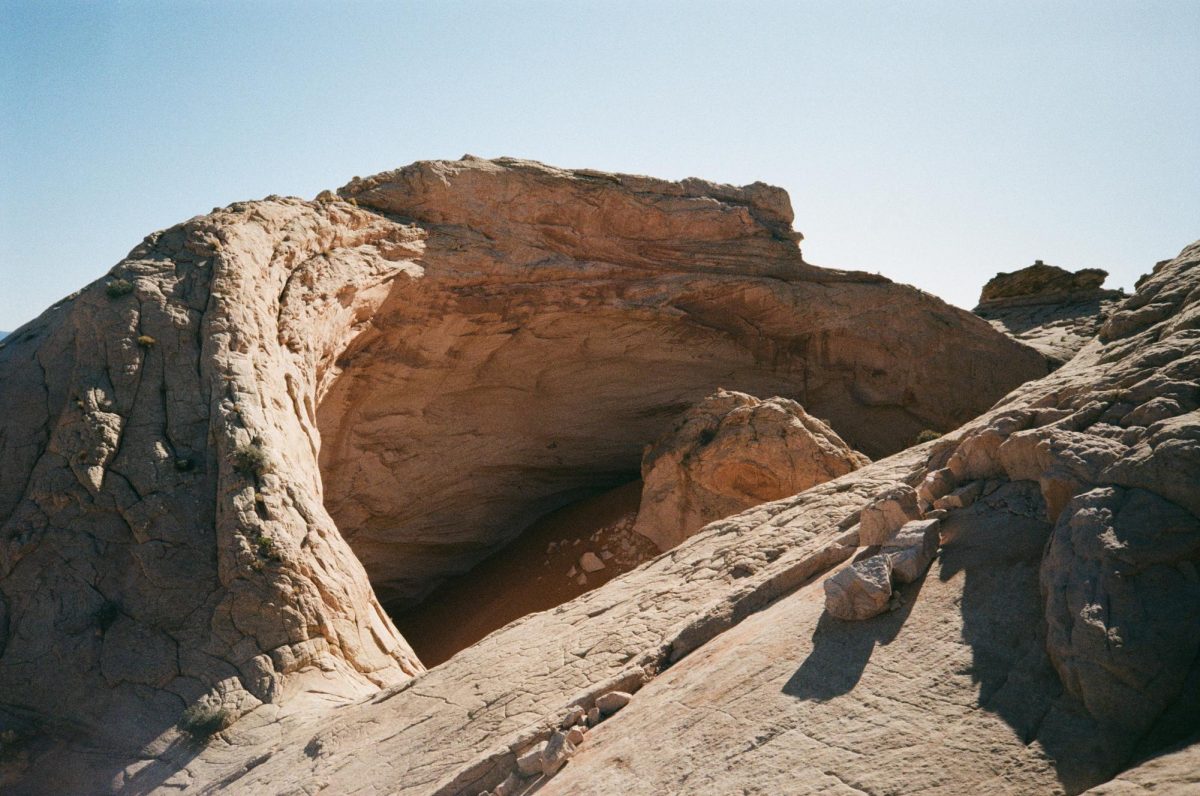

Nik Benko, bouldering in the desert.

April 18, 2020

I was home for the summer after my freshman year of college, working as a lifeguard at the local community college, when one of my friends texted me. There was this new 24-hour bouldering gym in town that he told me I needed to check out after work. I had no idea what bouldering was but was pretty bored from another uneventful day of sitting in a chair, so I decided to go see what it was all about. When we arrived, I filled out a waiver, paid for a guest pass, and opened the door between the front office and the gym.

The first thing that struck me as I walked through the door was the smell — a combination of aerosolized climbing-chalk, and lemon Lysol used to “clean” the climbing shoes that were available to guests. I grabbed a pair of loaner shoes from the rack, gave them an extra spray of Lysol and sat down on an old leather couch to put them on. In front of the couch, the entire floor was covered in padding and the couch faced a steeply overhung climbing wall that reached about 20 feet tall. As I put the shoes on, I watched a group of built sweaty men try to climb to the top of the wall on a particularly hard route. One after another they fell the entire height of the wall onto the pads. As someone who had recently overcome my fear of the high-dive, I decided these people must be insane.

I found my way over to a wall that seemed much more civilized at 12 feet high and tenuously climbed up on a set of large purple holds. When I reached the end of the route, I threw my leg over the top of the wall to top out and looked down at the padded floors with satisfaction. I then learned the basic details of the bouldering rating system and ran around the gym climbing all the V-fun and V0 routes on the few walls that weren’t steeply overhanging. I then moved on to attempt a few V1 and V2 routes and rapidly discovered that bouldering is actually really hard. After several hours taking turns on routes with a few friends, I left the gym with skin missing from both hands and arms so pumped up that I could barely grasp the steering wheel on my drive home.

A few weeks later, I cashed in my last paycheck from my lifeguarding job to buy a jacket, a tank of gas, and three weeks’ worth of food to hike the John Muir Trail from Yosemite Valley to Mt. Whitney. In order to secure a walk-in permit for the hike, I arrived in Yosemite a day before I planned on starting the hike. After setting up my tent in the backpacker’s camp, I walked the trail on the north side of the valley, passing by Royal Arches, the Swan slab, Camp 4 and the base routes of El Cap. I didn’t know much climbing history at the time, but it was clear that it was a place of many legends that I had yet to hear. The sun had set by the time I turned around to head back to my camp for the night. As the stars began to appear in the sky, a second set of constellations appeared on the walls surrounding the valley. Climbers perched thousands of feet off the ground were setting their own camps for the night, their headlamps creating bright stars twinkling on the granite faces.

The journey down the John Muir trail lasted 21 days, but it was the culmination of nearly a years’ worth of planning camping locations and food drops, testing gear, and trail recipes. At the age of 19, the solo hike was the greatest adventure of my life and by the time I reached Whitney Portal, some 220 miles from where I had started, I knew that I could succeed on just about any plausible backcountry hike. The only logical progression in backpacking seemed to me to be longer and longer trips in more remote areas — something difficult to accomplish as a college student and even more difficult to get motivated for after so much walking. What did strike my interest were all of the granite walls and peaks that I had passed along the way. Somehow between all the grandeur of Yosemite and reading Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air during my nights in the tent, I decided that becoming a climber was a good idea. When I got back home, I was back in the climbing gym the next day. Within a few months I had purchased my own climbing shoes and a harness, and for my birthday, I asked for a rope.

I spent the next several years slowly accruing bits of gear and learning the basics of outdoor climbing from setting top-rope anchors to lead climbing. Because I didn’t yet have any friends that climbed, I learned from reading books and watching videos on YouTube. By the time I had finished at UC Santa Barbara, I had enough quick-draws, nuts, and a few cams to get up most of the short, mixed climbs in the local hills. My skills had likewise progressed, but slowly as most of my climbing partners were indoor-only climbers and we were all a little preoccupied with living in the beachfront fantasy land that is Santa Barbara.

When I applied to graduate schools, access to climbing was a considerable factor for choosing which schools to applied to. After settling in Salt Lake City, I was excited to discover the wide variety of climbing available so close to town. For nearly everyone not named Alex Honnold, outdoor route climbing is a team activity so the biggest impediment when I first arrived was finding people to climb with. I quickly found that unlike the central coast of California, climbing is not a fringe sport in Utah and many of my fellow grad students became great partners. After a few trips to the sport crags in Big Cottonwood Canyon, we set our site on the white granite of Little Cottonwood. There, my friend Kiffer Creveling and I got a first a first-class lesson on the art of the sandbag by climbing the Crescent Crack, a traditional route that involves a poorly protected overhanging heel hook inside of a chimney. Should be pretty basic right?

The nature of trad climbing — where you place your own gear into cracks in the rock for protection — can make progressing to more technically difficult climbs challenging. When you need to be able to hold on in one position for long enough to place a piece of protection and clip the rope to it, it tests both your physical ability to hang on and your mental fortitude to trust that the gear you are placing will hold in the event of a fall. This, coupled with the high availability of high-quality easy routes in the Cottonwoods, means that it is easy to plateau in the 5.8 to 5.9 range of route ratings. However, longer climbing-routes on higher mountains tend to fall into one of two categories; they are either trivially easy from a climbing perspective and only involve scrambling over a long series of small ledges, or they are more technical routes in the 5.10 range and above. This summer, after spending the past several seasons in my comfort zone of 5.8 to 5.9 climbs, I decided to make it a goal to regularly climb 5.10 and begin to venture into 5.11 where harder climbing begins.

I decided that I simply needed to climb more, a lot more. Getting out for a pitch or two with a group of friends once or twice a month was not going to cut it. So, I hit the Mountain Project partner finder page to solicit strangers into climbing with me. Luckily, I was able to make a few connections and establish a new partnership that typically involves climbing outdoors once a week. With this increased frequency in climbing, I have successfully transitioned to regularly leading 5.10c on sight, and even made my way up my first 5.11a — with a few “takes” along the way. In the end, I have found this progression similar to ones I have made in the past and discovered a few helpful techniques that should help anyone who is looking to increase the grade of routes they are climbing.

- Find ways to climb often. This sounds like a no-brainer but it can be difficult to accomplish if you have more life obligations than a diehard climbing dirtbag. If you work a regular 9 a.m.-5 p.m. job this means learning how to climb in the dark. By purchasing a decent headlamp, you can extend the number of hours that you can climb after work during spring and fall enough to allow for several climbs. It can also mean getting up early on weekends. During the summer, it becomes far too hot to climb on south-facing aspects by 11 p.m. or 12 o’clock. By getting to the crag by 6 a.m.-7 a.m., you can fit in more climbs in the shade and be home with plenty of time to enjoy the day.

- Change up your partners. It can be easy to fall into comfortable patterns with established partners, returning to the same routes year after year. By switching up who you climb with, you may exchange showing each other your favorite routes that the other has never climbed before. It can also change your tolerance for failure. I’ve found that climbing with the same set of people after several seasons, it is inevitable that one or both of you will fail on a route. A new partnership can induce a bit of fear of judgment that is long gone with regular partners and can push you to try a little bit harder when the going gets rough. However, you should always place safety first over impressing a new belayer!

- Slow things down on the climb. Learning to rest on a climb is an important skill that takes time to develop. When I get to a good place to place gear, I often have the urge to place the piece and then take off right away for the next move. When you come to a comfortable stance on a harder route it can be highly beneficial to place the piece, clip the rope in, and then take a deep breath and access the route ahead. Try to spot where the good hand and feet holds are before you get to them. If you can decide where and when to place the next piece of protection ahead of time, even better.

- Know when to go. Sometimes, you just need to climb the damn thing. Unlike sport climbing, where bolts are usually placed at regular intervals for protections, with trad climbing it is up to you when to place gear. When you first start climbing harder routes, it can be natural to try to place more gear when you feel the route getting more difficult. This can often backfire as you will spend precious energy clinging tightly to a poor hold when there is a better stance a few feet higher than you would be able to get to if you just fired the moves straight away. By combining this technique with the one above, you will be better able to manage your strength throughout the climb and increase your chances of success.