Slack Lake City

October 23, 2019

“Are you training for the circus? Is that a tight-rope?” Slacklining is new in the adventure sports world and is gaining quite the audience. Originating from climbers walking along chains at trailheads, the sport attracts outdoor enthusiasts, adrenaline junkies, yogis and any other type of person not content with staying indoors. In a park, a slackline is made by stringing a length of webbing across two trees. This can be loose, tight, long or short, depending on your preference. For those who want to raise the stakes, step it up or get on a higher level, a line can be set up higher above the ground with multiple anchor points on either side for safety. From there, one would attach themselves to the line and be ready to go. This is called highlining. In Utah, you can find established highlines at the Fruit Bowl in Moab, Rock Canyon in Provo and Suicide Rock in Salt Lake. As highlining finds new participants in Salt Lake, more and more lines are being established, a recent one being the Stevie Knicks line in Big Cottonwood Canyon.

For being such an offline and outdoor sport, the slackline community thrives and grows online. You can find most slackline and highline information off of YouTube videos or Facebook groups. Any information not found online can be found by seeking mentorship from your locally established guru slacker. Slackliners seem to be always willing to teach those who ask kindly to learn. This creates a learning-centered community that supports slackers from all walks of life and levels of ability. In Salt Lake, you will find most of your routine slackers in Liberty Park. Some of the gatherings you’ll see are organized on the Salt Lake City Slackliners Facebook page. Salt Lake City Slackliners is a page of around 600 members who post their slackline whereabouts, and everyone interested can go and hang out. You can find the admin of the page, Jake Pawlak, posting new highline adventures every once in a while as well. Those who decide to join in are expected to contribute to the mission by helping haul gear, donate stoke or bring snacks.

Pawlak grew up in New Hampshire hiking with his family and mountain biking with his brother. Wanting to escape the East Coast, Pawlak decided to head out to Utah for college. During his freshman year, he learned the love of climbing and slacklining from his friends at the U. Pawlak didn’t start the Salt Lake City Slackliners Facebook page, but joined when his friend, an avid slackliner, told him about the page and how he can find more people to slackline with there. Like many people new to a community, Pawlak kept up with the page but didn’t participate for a few months. The first meetup he went to, he met someone who invited him to go highlining.

The next day, the highline was up, and Pawlak had never felt more terrified in his life. With blurry tunnel vision, he slid out onto the line. He got up, and through the rushing adrenaline, he took his first few steps and fell. The whipper fall and first-time jitters got Pawlak off the line for a quick break. After his second attempt, he was hooked. From then on, Pawlak spent his free time researching highlining, different rigs, and best safety practices. Along with research online, he spent his days setting up rigs with other highliners and learning as much as possible. Through Salt Lake City Slackliners, Pawlak found new slackline buddies. These people helped him learn more and more about the technicalities of slacklining and highlining. Throughout this time, Pawlak was chin-deep in school and taking life one step at a time. Slacklining was an escape, a way to relieve stress and find solitude.

For many people, slacklining can be a form of meditation and a way to center your thoughts. Others use slacklining to push themselves out of a comfort zone. The sport of slacklining is a challenge that can foster competitive experiences and personal growth. Spencer Seabrook, in the documentary “Untethered,” used the challenge of highlining to push the limits of his mind and body. “My body might be scared, but my mind isn’t scared, you know, and that’s kinda what you’re fighting for right there,” Seabrook said. Some say that you are never comfortable on a highline, and the only way to advance is to figure out how to push past that initial fear for as long as possible. Highlining is a way to directly confront your body’s natural response to stressors in life, such as a busy school and work schedule, speaking in front of a group of people or hanging from a climbing harness in the middle of a canyon hundreds of feet off the ground.

As a group activity, slacklining can create an amazing atmosphere. In southern Utah at the Fruit Bowl, the GGBY Highline Gathering is held every Thanksgiving and centers around learning how to advance in highlining and creating a social gathering with other highliners. As one of the oldest organized highline events, GGBY has evolved and changed into a unique experience, thus far not replicated in any other part of the world. Starting as a yearly get-together between a group of friends, GGBY has gained enormous traction and talent each year. As of 2018, GGBY is currently the only highline festival that is insured and licensed, all while working with the Bureau of Land Management to host a safe environment for the people and the animals and the environment. As a three-year attendee, Pawlak appreciates the festival’s recent efforts to work with authorities to minimize the human impact, even if it meant creating an entrance fee and enacting policies and guidelines for the festival. This year, to accommodate the growing number of attendees, more highlines will be set up.

Each year, a few people from the Salt Lake City Slackliners group go to GGBY together, meet up and enjoy the festival. During other parts of the year, Pawlak has taken trips with the group to rig the Fruit Bowl themselves. “It’s the same highlines, just with less people and more time,” he said. On one trip down to the Fruit Bowl, Pawlak rigged a 300-meter line under an overcast of clouds. During the 12-15 minutes it took for him to walk out there, a storm rolled in. After realizing the storm was overhead, he clipped in with his hangover (a carabiner with wheels which allows you to roll along the line) and took six minutes to get back to the cliff. “I’ll never rig in those conditions again. It’s okay to fail at things. I’ve had plenty of times where we plan a rig and had to call it off because we were not prepared. It sucks to have that happen but you learn something from failure.” For Pawlak and highlining, it is important to know when to stop for your safety. It is also good to know when you need to push your limits to get stronger, faster or just plain better.

On a trip in Joshua Tree, Pawlak and others set up a 330-meter line, a daring and intimidating challenge. The first day he had a really difficult time. Getting to the middle of the line took around 25 falls, each requiring him to climb up his leash, swing on top and stand back up with the intention of moving forward. All motivation was gone, and Pawlak was ready to clip onto the line and go back. After a moment, he gathered himself and knew he needed to walk the 330 meters. He sent the rest of the line, only taking a fall when the leash got caught up. The next day, Pawlak was able to work with the line and got into the flow. “It felt really good to not let myself give up that easily. I know now that when things are going bad, they will eventually get better. Keep changing what you’re doing to bring yourself back up and eventually you’ll be able to get out of it.”

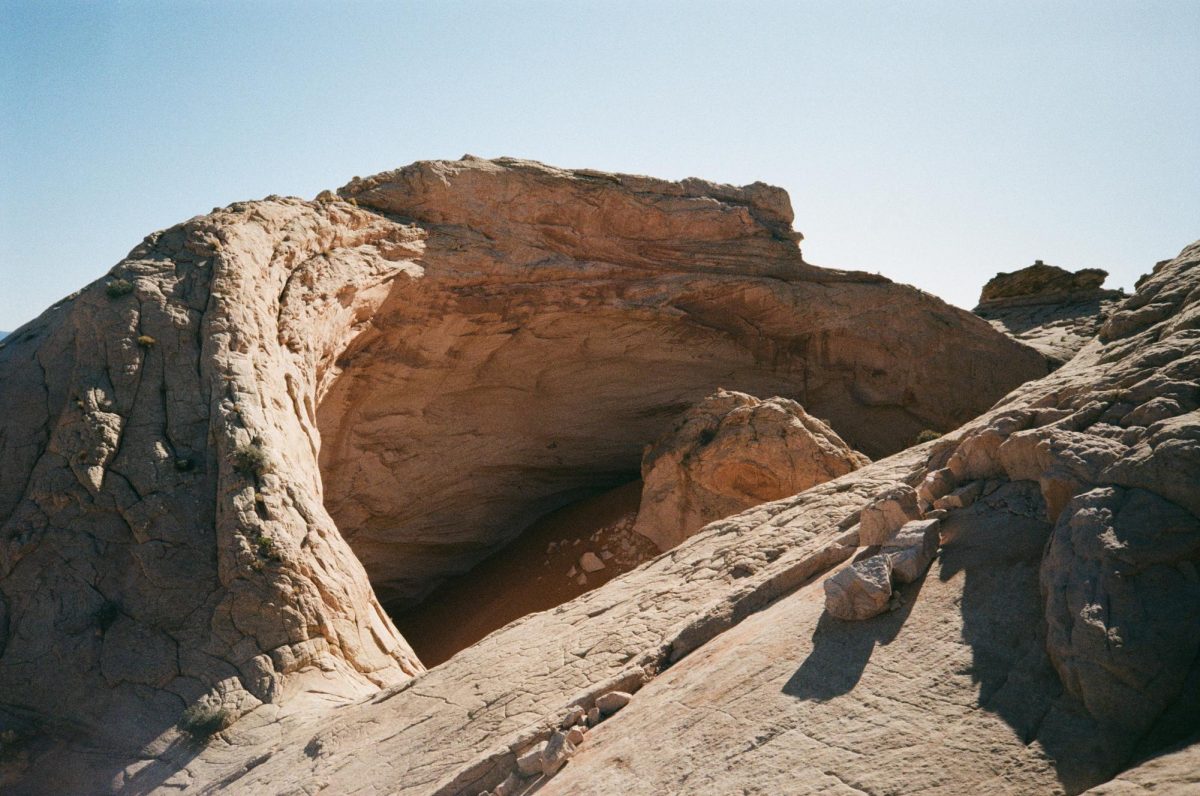

In early September, there was a post on Salt Lake City Slackliners inviting people to rig Rock Canyon in Provo for Labor Day. Headcount and head-out from the trailhead was at 8 a.m. Our group of four found ourselves scrambling up a trail on the west front of the canyon, to get to two juttings off a cliff. On the way up, the air was filled with curiosity about the existence of such a steep trail, and excitement for what was to come. We rigged for about 45 minutes before the 60-foot line was ready to go. The first walk of the day was from Brandon, who brought the gear and organized our group. After the first leash fall of the line, we all felt good about the line and settled into our rocky seats overlooking Utah Valley. As the music played over the wind blowing out of the canyon, each of us took our turns getting on the line, finding our comfort zone and pushing to find a new limit to our abilities. Each leash fall was met with a grin of success followed by the physically taxing task of climbing back on top of the line. Having never met these people aside from seeing their names pop up on a Facebook thread, I found myself walking away with a larger inkling of who these people were, what they stood for and why they highlined.

The challenge of highlining is impossible to face alone. A highline cannot be set up efficiently with one person. Most of the time, setting up a highline can be the greatest challenge of the trip. A team of people must work well together with all of the different variables to set up a safe and secure rig. When you step foot on any highline, you are double-checking the work and putting your life in the hands of the people who rigged the line. When things don’t work out, you have to be able to take a step back, accept that the highline won’t happen that day and plan the next trip. This type of trust and dependability that highliners have with each other can create strong friendships and connections. Each highline comes with its own challenges and technicalities, so much that teaching the ins and outs of that specific line can only be done in person over mentorship. Around the world, slackliners are connecting through the internet, meeting up and learning from each other. From Facebook pages to YouTube videos, slackline sessions and highline trips, slackliners around the world are supporting each other to push comfort zones, create adventure-filled memories and get stoked on the growing, thriving sport of slacklining.