The Confluence of Adventure and Academia

March 29, 2021

For college outdoor enthusiasts, outdoor recreation can serve as an outlet from the labors of being a student. Time spent outside is what drives many to study what they do. What a lot of students don’t realize is that the skills they spend time refining on the weekends could be utilized in their education or even future careers. I sat down with two professors from the University of Utah’s geography department to learn how they have been able to use skills derived from outdoor recreation in their research and to explore examples of where adventure and science overlap.

Dr. McKenzie Skiles has a Ph.D. in geography and has spent the past several years studying, in layman’s terms, the impact of dust on snow in the west. When she arrived at the University of Utah seeking a bachelor’s degree, she didn’t know that snow was even something one could study, but her interest in the topic came from a breadth of winter recreation experiences. “I didn’t really know a lot about the U’s academic programs when I came here — I just wanted to ski,” Skiles told me. Hailing from Anchorage, Alaska, Skiles describes skiing as her first love and acknowledges how that relationship only grew stronger during her undergraduate years. As she worked through her undergraduate and master’s programs, she also started taking avalanche classes and gaining experience in the backcountry. When the time came to contribute to research in the field and eventually design her own research, she was ready.

Fieldwork for Skiles entails digging snow pits, traveling to SNOTEL sites, flying drones and when she’s lucky, touring into the backcountry to analyze the snow at high elevations. Skiles explained that in the Wasatch, a lot of the study areas are within ski resort boundaries, meaning avalanche danger is largely mitigated. In the San Juan Mountains, however, she has had to focus a lot more on risk management and planning in order to make safe decisions regarding traveling in avalanche terrain. The mountain doesn’t care if you’re there for fun or for science, and sometimes her teams have bailed on research objectives for a certain day because of avalanche conditions. “I like to think I am always cautious,” she told me, “but there is definitely added risk when going into the backcountry with a team that might have highly varying levels of experience and is carrying heavy or expensive equipment”.

Another University of Utah professor, Larry Coats, is also familiar with managing risk in professional research environments. Coats is an avid skier too, but in his research career in the deserts of the Southwest, he has used technical ropework and skills from his climbing background. He first entered the research world as a climbing guide. After getting a bachelor’s degree in Psychology from Northern Arizona University, Coats spent the majority of his time climbing, writing for adventure magazines and working in a gear shop in Flagstaff where, in 1983, he met Steve Emslie, a paleontologist working in the Grand Canyon. Coats assisted Emslie in getting access to caves high on the canyon walls that held fossils and artifacts of ancestors to the Anasazi people. When I asked if Emslie was much of a climber, Coats sheepishly responded “oh-no” and chuckled. It seemed that one of the most simultaneously challenging and delightful parts of his experiences in research has been helping others reach remote places.

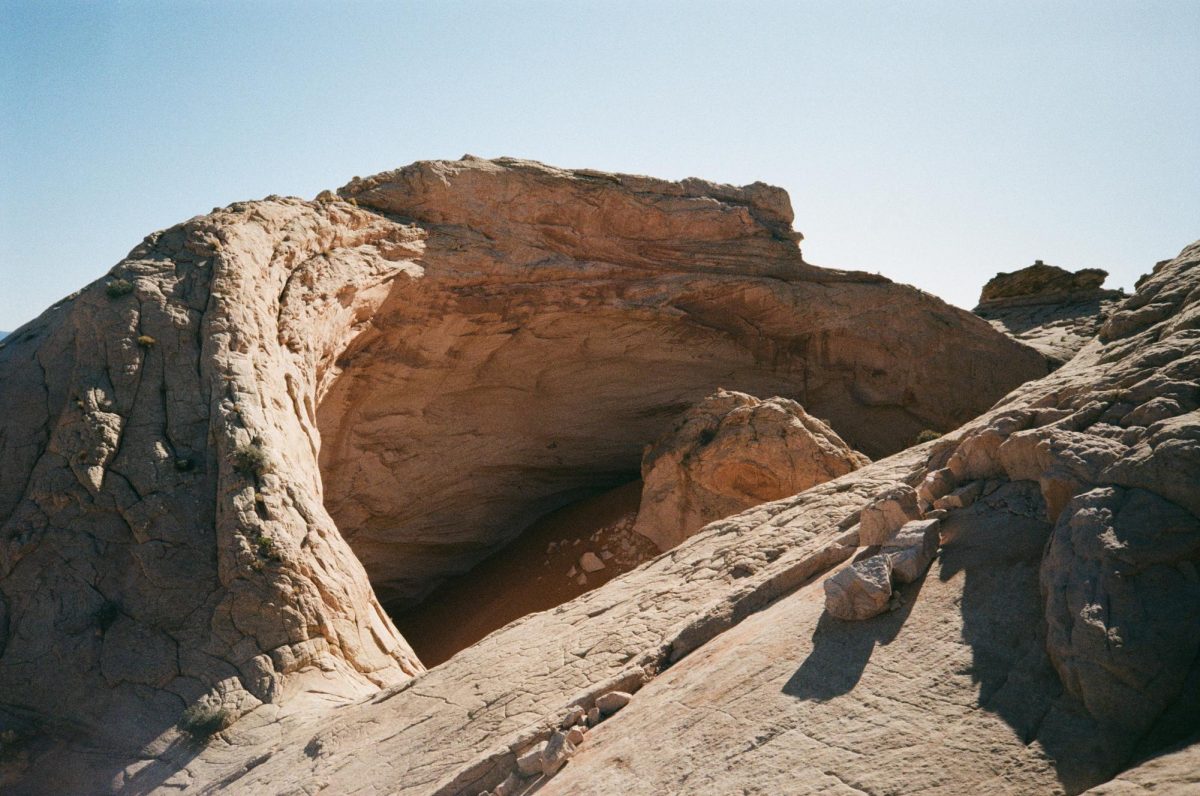

As a self-proclaimed “nerdy kid,” Coats had been interested in archaeology for most of his life. Exploring caves that no one had stepped foot in for thousands of years was right up his alley. He went on to spend almost a decade exploring caves in the Grand Canyon. Today, he serves as a member of a team of researchers from the University of Utah investigating the Fremont occupation of Range Creek Canyon and frequently rappels and uses rope skills to make the work more efficient.

Skiles and Coats both had plenty of advice for the outdoorsy college student trying to figure out how to make the outdoors a core part of their career. Skiles emphasized the usefulness of certifications and classes to not only build knowledge and confidence but also to boost application presentation. Having somebody with a Wilderness First Responder certification on a team is a requirement for several agencies, including the National Science Foundation, so getting that certification and keeping it current is a great way to stand out in a pool of academic research applicants. Having a strong outdoor recreation foundation only opens doors for researchers. If given the opportunity to design their own projects, the sky is the limit for people who are comfortable or willing to get comfortable pushing the boundaries of what scientists can achieve. Of course, there’s lab time and plenty of desk time involved for both of these adventurous researchers, but for folks whose sanity hinges on being in nature, getting to contribute to science and spend time outside is about as sweet as it gets.