The Joys of Solitude

September 12, 2020

All I can hear is the sound of my breathing in sync with the crunch of metal on snow. I slowly make my way up the slope, each step firm enough to ensure that the snowshoe has caught hold of the crust. With my legs burning, I reach the ridge line and a late evening sun hits me. I continue up the ridge line towards Ben Lomond Peak. Upon reaching the peak, I let out a “whoop” that only the swifts performing high-speed aerial feats around me can hear. I am the only human for miles around. I put on my parka and sit for some time to watch the sun sink towards a horizon that slowly turns to shades of yellow and orange. I feel a deep sense of peace and accomplishment. I can say, as Aldo Leopold dramatically wrote in his 1949 book A Sand County Almanac, “Never had there been so rare a day, or so rich a solitude to spend it in.” Feeling satisfied, I descend back to camp.

It was a moment known only to myself and the mountain. While I was up on Ben Lomond Peak, I could look left of the sunset and see my parents’ neighborhood down in the Ogden area. Like many other students at the U, I moved homes in March when classes went online. With extra time on my hands, trails close by and no one else to get outside with, I started mountain biking and hiking alone. While I happily spend much of my time outdoors in the company of friends, COVID-19 presented an opportunity for me to explore the benefits of solitude. It was social distancing at its best. I’ll admit, as a more introverted person, I welcome the opportunity to spend time alone. However, I don’t think the benefits of solitude are limited to just the needs of introverts. I understand the limitations of my perspective, but I believe finding time to go out alone can be valuable for everyone.

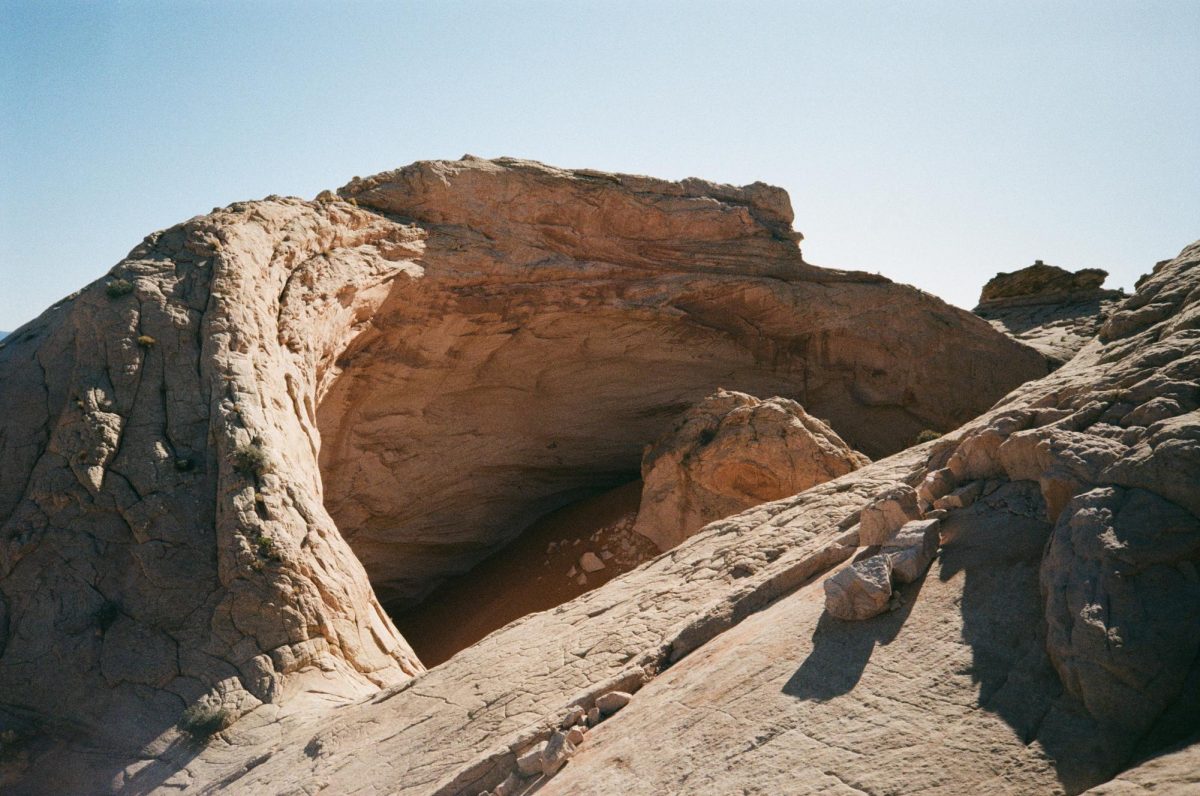

Leopold spoke of solitude as a kind of natural resource. How can it be a resource? Why would we want to spend time alone in nature? Rather than seeing it as a resource, can we view solitude as being scary? In the book Mountains of the Mind, Robert Macfarlane quotes the writing of an 18th century man named Dr. Johnson. Speaking of his journey to the top of a mountain in England, Johnson remarked that in such a place, one “has not the tranquility, but the horror of solitude, a kind of turbulent pleasure between fright and admiration. The ideas which it forces upon the mind, are the sublime, the dreadful, and the vast.” Sometimes there is a kind of horror in isolation. If I told someone that I feel alone, they would be worried, not happy for me. Loneliness is a human emotion we fear. Macfarlane wrote that “you could be lonely in a city crowd, but you could find solitude on a mountain-top.” Solitude and loneliness can be distinguished as the joy and pain of being alone, respectively. Maybe we are more likely to feel loneliness within a crowd than we are in the wilderness. Solitude can be solace when we make the choice to go alone. Spending time in solitude can be a welcome respite from the stress of our daily lives, rather than a reason to immediately yearn for human contact again. We can embrace the solitude, including the scary and the peaceful parts. When we return home, we might find ourselves feeling greater appreciation for the people we care about. I haven’t spent more than one night alone. Most of my solo adventures have been day hiking and mountain biking. For this reason, I can’t speak to the mental challenges or benefits of longer solo trips. What I can speak to though, is the importance of spending chunks of time alone in nature. There are four main reasons why we should embrace solitude.

Self-reliance

When weighing options and making decisions in the outdoors, second opinions and deliberation are valuable. In the absence of any second opinions on solo endeavors, I have to trust my own conclusions. As a result, I try to withhold making any decision until I have carefully, patiently analyzed my options. Humans make mistakes. Things don’t always go as planned. But over time, our self-confidence will grow as we make good decisions and have great adventures. We can learn to trust ourselves and become self-reliant. This self-reliance can also help us regulate stress and stay calm when we may be sore, tired or generally having a hard time. More practically speaking, in order to be safe when I go outside alone, I plan carefully and make sure I don’t push myself too hard. Beyond the regular safety items like a first aid kit, rain protection and other items — I also personally bring a satellite rescue device that can act as a last resort if self-reliance ultimately fails.

Psychological Benefits

Dr. David Strayer, a psychology professor at the University of Utah, focuses part of his research on how spending time in nature affects the human brain. In his 2017 Ted talk “Restore Your Brain with Nature,” he explained how nature can act as a restorative tool in brain function. He spoke of multi-tasking as a problematic side-effect of our near constant use of technology in the modern world. Multi-tasking happens in the pre-frontal cortex of the brain. Overuse of this part of the brain through multi-tasking causes fatigue. The pre-frontal cortex is also responsible for tasks such as critical thinking, problem solving and decision making. Dr. Strayer’s research shows that spending time in nature without multi-tasking helps to rest our brain and restore its capacities. As he stated in the talk, specific benefits of this are “improved short-term memory, enhanced working memory, better problem-solving, greater creativity, lower levels of stress and higher feelings of positive well-being.” When we go out alone in nature, we are minimizing distractions more thoroughly than when we go with a group. Technology, conversation and social dynamics are entirely removed. While conversations are important, there is a time and a place for everything. Sometimes it’s good to disconnect more completely. Being alone maximizes the restorative benefits of our time spent in nature. Our brain needs rest so that when we return to a chaotic world, we are more prepared to perform at our best.

Meditation and Clarity of Mind

Meditation in its most romantic form conjures up images of stoic figures upon high mountain tops, by the ocean or in other places that offer a beautiful or expansive perspective. I am not immune to the temptation of these romantic ideas. While meditation can be done in many settings, I usually feel more at ease in true solitude and among nature’s beauty. My aforementioned ascent of a mountain was a kind of moving meditation where I focused attention on my breathing and footfalls. This focus on the steady flow and rhythm of movement is a powerful way of connecting the mind and body. This sort of moving meditation can happen while running, biking or performing any outdoor activity. On the summit, I became more mindful while I sat and surveyed the landscape which spread to the horizon in every direction. Sometimes it takes me a long time to push away the part of my brain that doesn’t feel busy enough when staring off at the horizon. I have to remind myself that it’s perfectly okay to just let go; that it’s okay to let my guard down. Once the fist in my brain unclenches, I let thoughts pass through of their own volition. The stress begins to melt away, and the peace of those moments begets a kind of bliss. It is important to note that meditation is unique to the individual. For me, the solitude of wild places combined with the practice of meditation has been extremely beneficial.

Awareness and Inspiration

Often, I’ve had the experience of getting back to the car with friends after a day in the mountains only to realize that I didn’t remember many details about the trail, plants and scenery where I spent the day. I don’t find myself regretting the time I spent focused on the people I was with, but I do want to return to that same place again so that I can pick up on details I overlooked. Solitude-induced meditation in nature can leave us in a state of greater sensory awareness of what’s around us. I’ve found that while I move through terrain in a meditative state, I see, hear, smell or feel things I’ve never noticed before. I might notice for the first time a strange play of light on water, the scale-like leaves of a juniper, the bloom of a forget-me-not or the unique song of a Canyon wren. The more we take in, the more we can find appreciation for the diversity of life and landscape around us. In going alone, we may also see more wildlife that isn’t frightened away by the quiet footfalls of a lone traveler. All the plants, insects and animals around might even lead us to question how alone we really are when away from the city. Seeing the landscape with new eyes may open new channels of inspiration or insight within our minds. I like to bring a notebook along with me to record what I see, feel and learn. In writing down my thoughts, I can return home with physical evidence of my well-fed mind.

To quote Macfarlane once more: “All visitors to altitude were drawn in part by the conviction that they would be rewarded both with far sight and with insight: that mind-scapes as well as landscapes would be revealed to them.” Nature becomes much more inspiring when we take the time to go alone.