The Philosophical Dirtbag

March 29, 2021

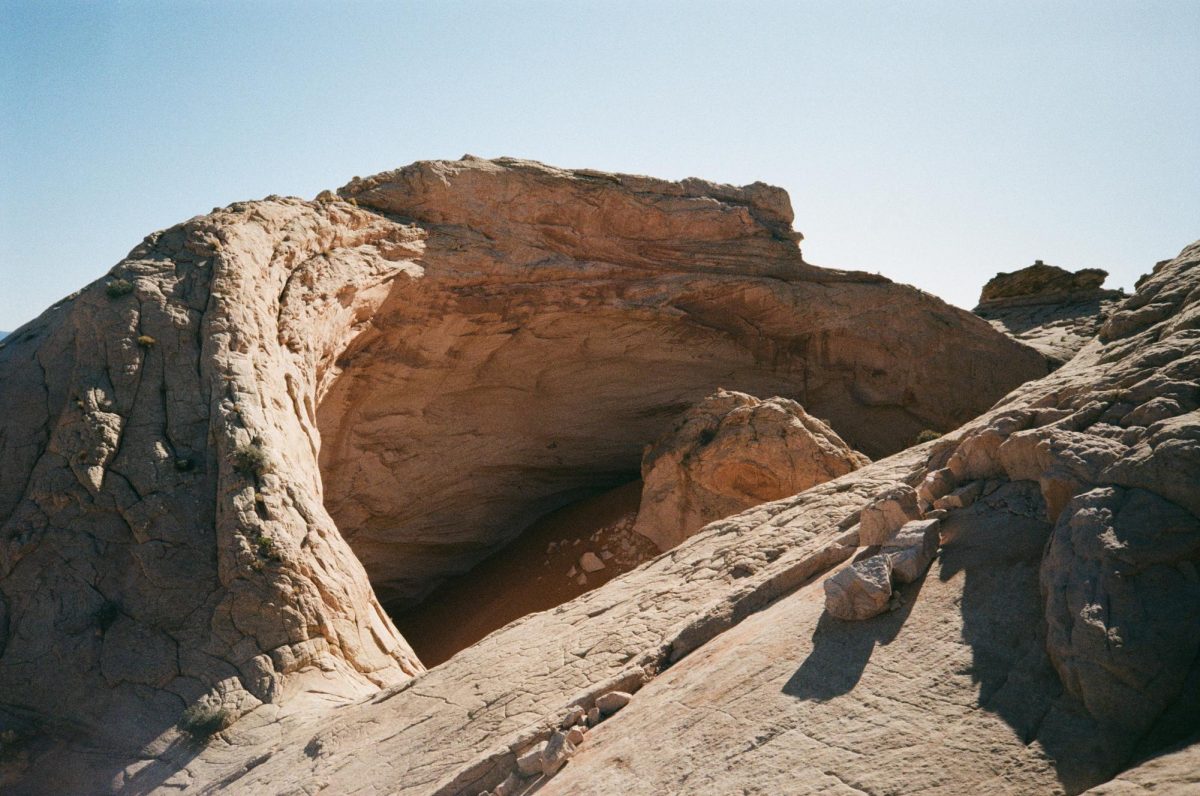

Have you ever looked up from your daily commute in Salt Lake City to find yourself face to face with a National Geographic-worthy view of the Wasatch? It makes the routine a little more bearable, right? There’s a certain quality in the outdoors that minimizes the dissatisfactions and anxieties of our lives within the manmade world. This feeling occurs in an even greater scope when we completely immerse ourselves in the natural world and come to find beautiful and dynamic places in which your GPA, paycheck and neighbors all cease to matter. The outdoors have this power to take us outside of ourselves — to make us feel both insignificant and infinite. I have sometimes found this feeling to include a physical sensation, similar to the weightlessness in your stomach on the first big hill of a roller coaster. It’s somehow both overwhelming and calming at the same time. I have also described such a moment as “so beautiful it hurts.” There’s a sense of clarity, interconnectedness and smallness all at once.

As I studied poetry — both on my own and in pursuit of a degree — I found I was not alone in my sentiments. Authors from the Romantic and Transcendentalist literary movements expressed this same feeling, coining it “the sublime.” William Wordsworth advocated for a love of nature in order to achieve a love of humankind. He used the feeling of the sublime as a springboard for both personal and societal reflection. In his collaborative collection with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lyrical Ballads, “Lines written a few miles above Tinturn Abbey” deals with this concept. Here’s a small excerpt describing the sensation of “that blessed mood.”

And even the motion of our human blood

Almost suspended, we are laid asleep

In body, and become a living soul

This poem considers the effect of nature on the speaker’s mind. He describes an ability to see more deeply and clearly as the weight of societal anxiety and chaos falls away in the presence of the landscape. It’s certainly a feeling I believe we have all felt on some level. The poem later compares the way Wordsworth played in nature as a child with his adult experience of the sublime. Frenzied and excited, it offered him an escape. As he grows older, he notes that his experience has changed, but not for the worse. Instead, he now loves the greenery and blue sky as an inseparable part of himself. To spend time outdoors is to find access to his purest thoughts and purest self. The physical self — perhaps the one we present on a day-to-day basis — is “laid asleep,” while the truer self — the soul — wakes up when in nature.

Wordsworth was writing during what we now refer to as the Romantic movement. Romanticism is marked by a love and reverence for the natural world, paired with a belief in the individual. The era peaked between 1800 and 1850. Transcendentalism developed around this time, focusing on and heightening the sentiments around nature and humanity. It’s Romanticism on steroids. They rejected the prescribed methods for happiness and success, contending that anyone can contact a higher plane in nature through these sublime experiences.

The most well-known transcendentalists include Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. I find that Walt Whitman also wrote with an unabashed love for nature and humans, forging an almost spiritual connection between the two. The opening lines of his renowned and expansive poem, “Song of Myself,” describe sitting in a field of grass, perfectly at ease. It observes that “every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you,” and continues, “I loafe and invite my soul.” Whitman invokes two beautiful sentiments here. First, that natural spaces are shared, not just by humans but by everything that lives. Second, these spaces provide an environment where a person can experience the purest part of themselves, very similar to what Wordsworth described. The poem goes on to explore the feeling of being in harmony with everything. We’re seeing the same feeling of interconnectedness; feeling infinite and yet insignificant next to the regulatory systems in nature. The grandness of the natural world offers this complex feeling. The world is large and indifferent to your presence, but there is also comfort in realizing you are genetically woven out of the very same material and thus part of a larger web of beauty and purpose.

What is it about these feelings that are desirable? I have wondered why I spend as many days as possible chasing the sublime; chasing that gut feeling achieved by standing still. A couple of months ago on a backpacking trip, my sister Sammie mentioned something about an evolutionary mismatch between the human brain and the societies they’ve built. Following that conversation, I did my own research, reading psychology papers and scientific articles. The general tone of my findings is that human psychological mechanisms developed in an impressively different environment than the one they function in now. “Evolutionary mismatch” is the term used to describe how traits that were once advantageous can become maladaptive because of a changing environment. Studies often discuss it in terms of diet or really any type of pleasurable consumption. In a primitive environment, all the ingredients of our favorite junk foods would have been difficult to come by. Psychological mechanisms developed in order to motivate survival, so we have a positive response to calorie-dense foods with fats and sugars. Now that those things are a readily available commodity, you can see how our mindset toward them has changed drastically. Anything that sells easily is capitalizing on the wiring in our brains, so to speak.

What does all of this have to do with the sublime? Since our brain shape and chemistry evolved in a much less developed, regulated environment than the modern context we’re thrown into at birth, I think the “sublime experience” that has fascinated thinkers since the nineteenth century is, in part, simply exposing our minds to an environment that they are wired to exist in. Maybe we encounter that perfect match between brain and environment with so little frequency that it is a sort of jarring sensation.

There are other ways to look at this concept as well. The University of Utah’s very own Professor Nalini Nadkarni has done fascinating work with implementing nature programs into prisons. Her research has shown, for example, that inmates who viewed nature videos committed 26% fewer violent infractions in Washington penitentiaries. It is likely that these facilities will have lower recidivism rates in the coming years as well. Other studies have linked time spent in nature to lowering high blood pressure and reducing anxiety.

I believe all of it — the research on nature’s ability to heal, potential for rehabilitation, theories of evolutionary mismatch in humans and poetry’s examination of the sublime. They are all facets of the purity of experience found in nature. That’s the feeling I search for when I go outside. ”

To finish on the note of poetry here is one of my original pieces. Enjoy!

Local Colossus

Beyond the boxed bricks of buildings,

Looming, jutting, growing, rises the familiar backdrop.

Kaleidoscopic cottonwoods flutter and fan,

Their soft pollens caught up and rushed to proliferation;

Their carriers collide with these hillsides and fly

Coldly following an exponential contour.

The skies obey these colossal and mountainous behemoths.

The atmosphere traces the crags sharply,

And atop every mammoth a summit spotted,

Surely each scrapes or kisses the exterior of our sphere,

Converging to ultramarine reaches unknown.

In superiority and ascendancy they seemingly soar

And in varicolored Olympian glory offer their fortitude.

Our robust firmament is an unashamed display of authority.

How strangely sublime to abide among giants,

To breathe the wind that finesses titanic precipices.

Cascading couloir and canyon carved glacially

And anciently brimming with gelid history,

The incessant wrestle of survival and enticement,

I am rapt with an ensuing obsession:

The pressure of earth underfoot.