Glen Canyon is a striking series of canyons carved by the Colorado River and its tributaries. The Colorado River once flowed freely, until 1963, when it was stunted by 710 feet of sheer concrete. More than 250 archaeological sites and traces and sacred artifacts of Native American tribes were washed away when the Colorado River was dammed, drowning the pristine experience of Glen Canyon and all of its rich histories in hundreds of feet of water. The dam remains a central subject of modern environmental movements now and decades back. Some of the best-known defenders of the west include Katie Lee, Edward Abbey, David Brower, and more. They are no longer alive, yet the story lives on through their legacy and the impacts they’ve had on those still alive today. These are their stories.

It was March 1981. Edward Abbey sat in the back of a pick-up truck and exclaimed: “Surely no man-made structure in modern American history has been hated so much, by so many, for so long, with such good reason, as Glen Canyon Dam.” He and others were gathered in Page, Arizona, or what Ed referred to as, the “shithead capital of Coconino County.”

The day is revered by many as the birth of the radical environmental movement in America. Members of the Earth First! environmental group unraveled a 300-foot tapered black sheet of plastic down the front of the dam that simulated a gigantic crack.

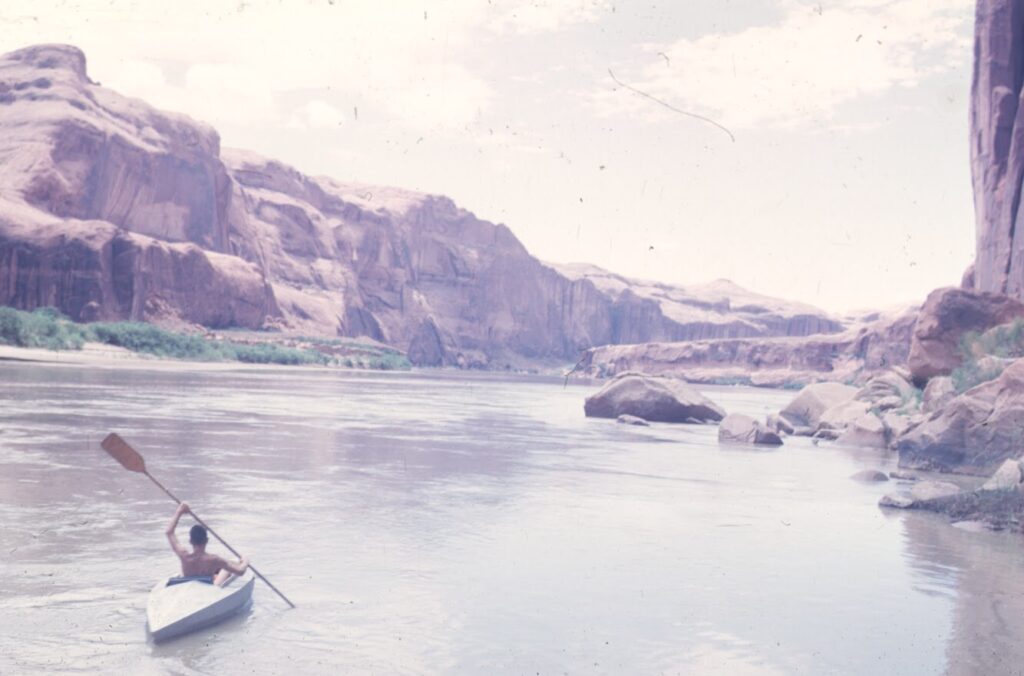

Glen Canyon has been the focal point of recreation and controversy in Southern Utah and Northern Arizona for many years. Notable activists have dedicated their lives to advocating on behalf of these places, like folk singer and river runner Katie Lee. “Rivers are the lifeblood of our planet and they need to flow,” she said in a 2016 biographical short film titled “Kickass Katie Lee.”

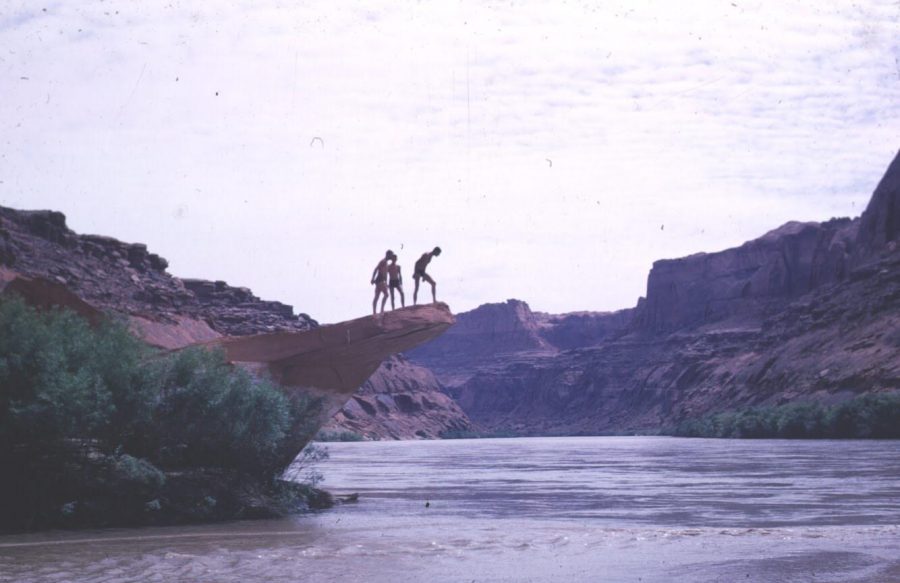

Katie spent much of her life exploring Glen Canyon and the Colorado River before it became “Lake Foul,” as Ed described it. Some call her “the Desert Goddess of Glen Canyon,” and she is famously known for her nude photos, seemingly aligned with the sandy curves of the towering red rock canyons.

Katie spent much of her life exploring Glen Canyon and the Colorado River before it became “Lake Foul,” as Ed described it. Some call her “the Desert Goddess of Glen Canyon,” and she is famously known for her nude photos, seemingly aligned with the sandy curves of the towering red rock canyons.

Katie and Ed joined forces with folks like David Brower—the executive director of the Sierra Club—to demand the canyon be restored to its original, pristine state, which meant draining Lake Powell and letting the Colorado run free again. Decades of activism before and after the damming of Glen Canyon have served as the subject of many photography projects, pages of literature like Desert Solitaire, and the focal point of modern films such as Damnation.

There is no doubt that in a fast-paced world, many of us flock to the wilderness for an experience contrary to everyday life. We crave solitude, silence, serenity. In the bustle of the city, we crave untouched places of the world, free from human manipulation and destruction.

Carrying the Torch

Rich Ingebretsen is one the few who explored Glen Canyon before it was flooded. The first time he went there, he knew these areas were going to be flooded. “It made me sad,” he said. But years later when he navigated the same canyons by water, remembering their former state, “This made me mad.” So he founded the Glen Canyon Institute. The purpose is to “promote discussion, develop science, create a library of images, prevent further destruction, and look at the possibility of restoring Glen Canyon,” said Rich.

Rich described Glen Canyon as being “more than beautiful, it was spiritual. The sounds and the sights made it a reverent place. There was nothing like it on earth. I have hiked in Cataract, and Marble and the Grand Canyon above and below it many times as a river guide. They have their own wonder, but nothing was as intimate and delicate as Glen Canyon.” The hope is that “as it is restoring, people can get a glimpse and perhaps a sense of what it was like.”

Rich has seemingly integrated the outdoors into every aspect of his life. He is the vice chair of the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, founded Wilderness Medicine of Utah to teach backcountry medicine, and owns an education river trip company called River Bound Adventures. He is a professor in the University of Utah Department of Physics and is both a professor and the program director of the Wilderness Program for the U of U School of Medicine. He is an attending emergency room physician and is the medical director of Salt Lake County Sheriff’s Search and Rescue.

In his life, Rich has worked alongside many local legends and together they pursued their goal of defending the natural treasures of the American West. “David Brower was on our board and Katie Lee was on our advisory board. I worked very, very closely with both of them. David was a visionary while Katie was strident. They were both ‘lions’ in the autumn of their lives. Katie could be angry, David could be reckless. But that is how they became who they were,” said Rich.

“When I picked David up to speak at our first Glen Canyon Institute event, he spoke to 1,800 people in a packed house on the University of Utah campus. When I picked up him up at the airport I told him that we were going to go after the draining of Lake Powell. And he said, “Oh, I have been meaning to take care of that, as though it was something simple on his to-do list. Katie sang and moved the entire house. 10 days later, David had the board of directors of the Sierra Club vote to ‘drain the reservoir behind Glen Canyon Dam.’

The reverence of Glen Canyon lives on through people like Katie, Ed, David, and many others who have passed away, yet who leave a legacy. And, of course, through people like Rich, who still advocate for the Colorado River and share the stories and history of what once was.

A Radical Historian

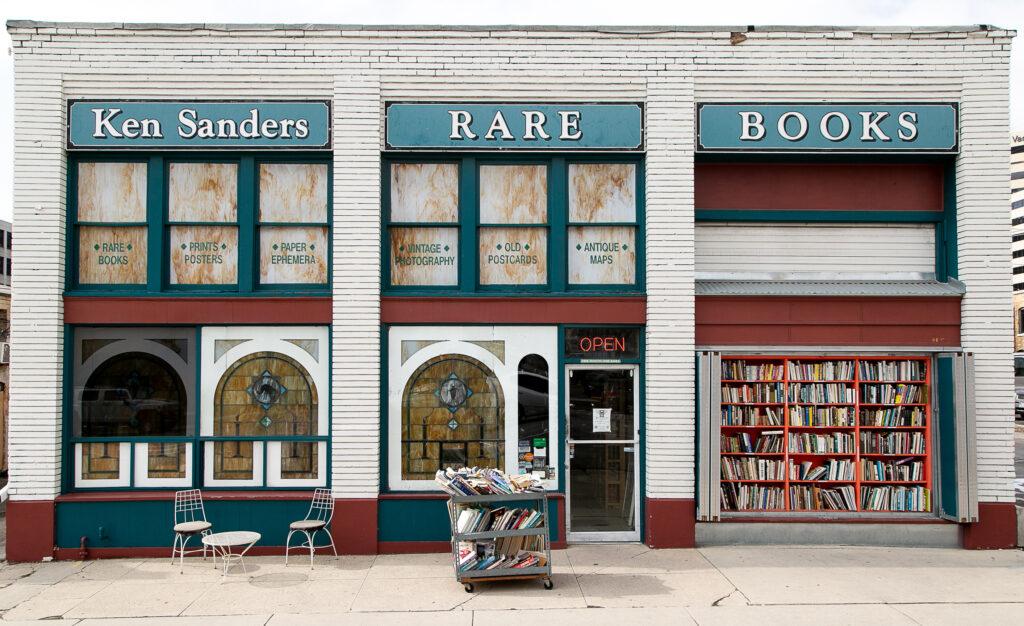

Another of these notable assets is Ken Sanders, who owns Ken Sanders Rare Books in downtown Salt Lake City.

If you’ve been to Ken’s shop, you have probably seen Monkey Wrench Gang and Ed Abbey references spattered throughout the shop and Ken’s website, a nod and homage to Ed and the friendship they shared. “Yeah, Ed Abbey was a friend of mine,” said Ken. “Ed and I had a lot of adventures together back in the day, he was—and is—a big influence on my life. He will have been gone for 30 years in March of 2019. There are two forthcoming books coming out on Abbey, and I have several thousand-word essays in both of them. Ed introduced me to the radical enviro group, Earth First!, in the spring of 1981,” Ken said, reflectively.

It was that same spring in 1981 when Ed gave a compelling speech at the “cracking” of Glen Canyon Dam, one of the first public events by Earth First!.

As a historian and environmentalist, Ken is well-aware how environmentalism and literature in Utah have gone hand-in-hand over the years. Ken’s shop is home to photography, art, and books new and rare alike, focused on radical politics, the sixties, sustainability, poetry, modern literature, and more.

A significant portion of the store is dedicated to Western explorations and travels, carrying “a healthy stock” of Utah-specific books, ephemera, photos, posters, prints, maps, and postcards, etc. on Utah and the Mormons—”it’s certainly one of our specialties,” said Ken. “We are passionate about the history and exploration of the West and its natural and unnatural history.”

In Ken’s words, “Everything is a treasure. Always collect what you personally love and treasure. Worth and value are immaterial and beside the point,” said Ken. This is a philosophy that can—and should—be applied to protecting the planet and our most treasured national monuments and wilderness lands.

Ken is not alone in this belief. It is shared among the many poets, novelists, and essayists who line the shelves of his store, many of whom are included in the extensive sections on the Colorado River, the Grand Canyon, and Glen Canyon. Some include Edward Abbey, Wendell Berry, Charles Bowden, Wallace Stegner, Terry Tempest Williams, Ellen Meloy, Rachel Carson, and more.

Ken has and still shares close friendships with many of these writers. “The Kentucky poet-farmer Wendell Berry remains a good friend and a huge influence on my life today. As did the late Charles Bowden, one of the most fearless writers in America. And Terry Tempest Williams has been a friend since she was a girl. I have privileged to know and have known some of the best writers, musicians and artists around,” as he lists them:

“Doug Peacock, Ken Sleight, Amy Irvine, Katie Lee, Rosalie Sorrels, Utah Phillips, Tom Russell, Ellen Meloy, Kate MacLeod, William Eastlake, Jim Harrison, Barry Lopez, John Dunning, Ken Brewer, David Lee, and oh so many more.”

In his line of work, Ken has been in a unique position to track the history of environmentalism and western wilderness through his collections, relationships with other local environmentalists, and his deep personal connections to the region.

“Southern Utah and the Colorado Plateau—along with the Great Salt Lake and the Great Basin Desert—are some of the most unique landscapes on the planet, said Ken. “Spend a day anywhere out there and you’ll discover why we need Escalante Wilderness, Bears Ears, San Rafael Swell, and all the rest,” said Ken. “Read Wallace Stegner’s, “A Wilderness Letter,” for one of the best articulations on why we need wilderness, whether we ever set foot in it or not,” said Ken, quoting Ed. “We lost a unique landscape when Lake Powell drowned Glen Canyon. And we won’t see it back, at least not in my lifetime.”

A Dam Big Controversy

Ken is right, but so many people still wonder about the fate of Glen Canyon Dam. Will a day come when Lake Powell is drained? What are the long term effects of the dam, and what will it take to see a healthy, free-flowing Colorado River once again? How do we prevent the fading of a history that once was—and is still, to many—considered a diamond of the west?

Protecting these places isn’t easy—it’s simultaneously a battle of politics, ideology, and special interests. Controversy seems to unravel at the expense of our natural wonders, including the damming and draining of Glen Canyon. For example, some argue that it would jeopardize Lake Mead’s long term viability in drought, or that it would cost the West thousands of jobs, millions in revenue, and put certain wildlife populations and riparian areas in the Grand Canyon at risk.

But, “Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell are temporary structures,” said Rich, which he describes as “some of the most destructive things ever created by man.” To put it simply, Lake Powell is not needed. “The water behind it has not been used. It is an accounting question, not a practical one. The dam exists for political and philosophical reasons only.”

The dam drives “the fear and mistrust between the upper and lower basins on the Colorado River,” said Rich. “Had they not divided the basin into these basins, they would never have built that dam, and the world would be better.” Contrary to what some believe, Glen Canyon Dam produces very little power, and could easily be reproduced if the water were stored in Lake Mead,” said Rich.

Glen Canyon Dam is less of a power production issue, and more of a “water issue and how water can be best delivered downstream without wasting it,” said Rich. “Lake Powell leeches and evaporates so much water that the water managers wonder if it is worth keeping. Up to 8% of the river flow each year is lost—more than three times Nevada’s entire allotment of water.”

Right now, Lake Powell is less than half full and continues to get lower and lower each year, yet “at the same time, it is being filled with sediment,” so, “the only reason that the environmental movement matters now is that we are based in sustainability,” said Rich. “Our data and vision provide long term solutions for western water, while at the same time allowing one of the most wondrous places on earth to restore, giving the area long term and sustainable economies.”

While it seems environmental activism continues to take on new forms, with renewed energy, there is no time to waste. “The time to get involved is right now,” said Ken. Right now, The Bureau of Reclamation is preparing new operating rules to govern how water is maintained and delivered from Lake Powell and Lake Mead. If you took all of the water in Lake Powell and put it in Lake Mead, it would not fill it. There is not enough water.”

It’s pretty simple: “The nation has overbuilt dams on the river,” said Rich. A solution is being proposed by scientists to address to lack of water on the Colorado River. It’s called Fill Mead First. Basically, it suggests that if you take “most (if not all) of the water in Lake Powell and move it to Lake Mead, there would be less water loss, more power generation, and restoration of Glen and Grand Canyons,” said Rich.

Don’t let the fight for Glen Canyon dry up—”people should visit www.glencanyon.org and get involved and let their voice be heard to restore these spectacular canyons,” said Rich. David Brower once said, “We must begin thinking like a river if we are to leave a legacy of beauty and life for future generations.” Take a part in protecting and sustaining the unspoiled places and experiences like an unflooded Glen Canyon and the wild drifts of a freed Colorado river. Because, in the famous words of Ed Abbey, “Love the land—or leave it alone.”