Touring Desert Peaks: What Makes the La Sals a Dangerous yet Rewarding Place to Ski

February 17, 2020

On January 25, 2019, tragedy struck a small southern Utah community. It had already been an especially snowy winter across the state, and January was no exception. Over two weeks, nearly three feet of snow fell in the La Sal mountains — a small, isolated range in the southeastern corner of Utah. On Friday morning, eight snowmobilers from the nearby town of Monticello ventured into the mountains in search of fresh powder.

Only seven returned home.

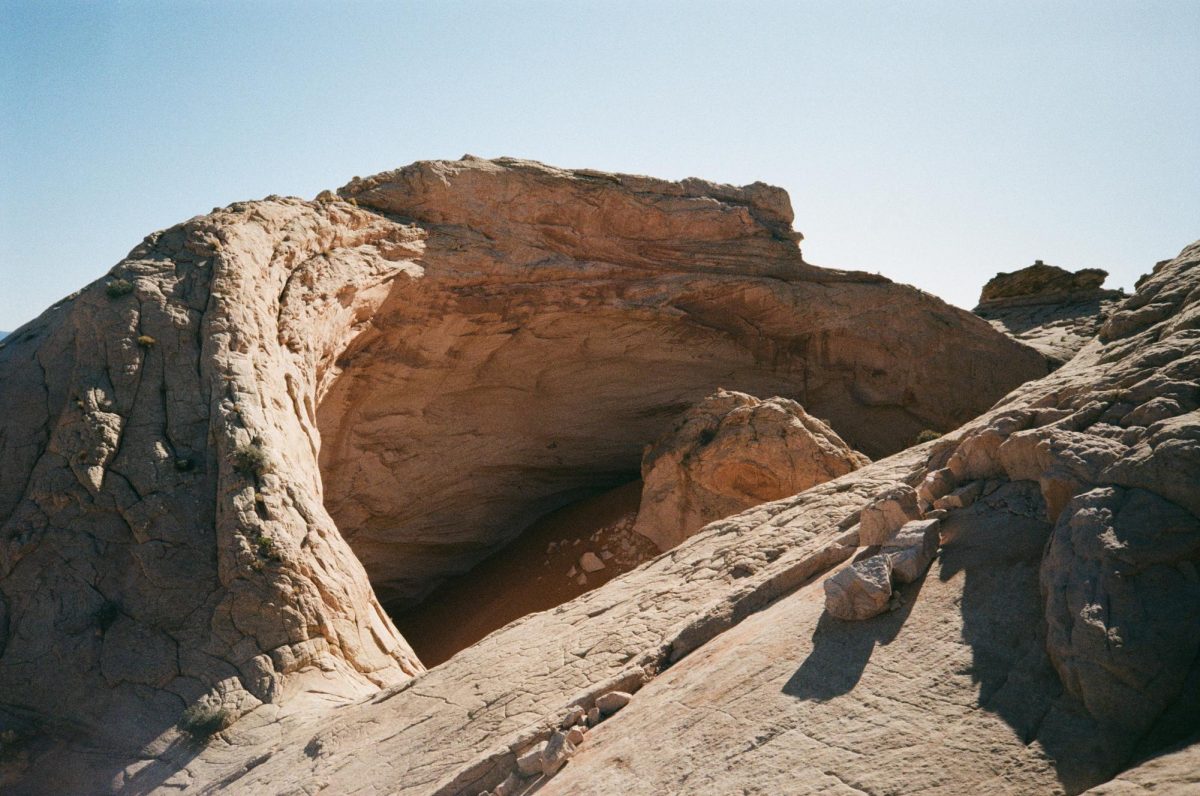

With peaks surpassing 12,000 feet, the La Sals tower above the famed desert town of Moab. The stunning contrast of red rock desert and snow-capped peaks is an essential piece of Southern Utah’s iconic landscape, portrayed on the state’s ‘Delicate Arch’ license plate. With their proximity to Arches and Canyonlands National Parks, the La Sal’s are one of the most unique mountain ranges in the country.

In the summer months, outdoor enthusiasts flock to the La Sal’s to hike, mountain bike, hunt, or simply escape the blistering desert heat. In the winter, the small, steep mountain range boasts a backcountry skiing experience that rivals that of the Wasatch.

But any seasoned Utah backcountry skier will tell you the La Sals are infamous. As an isolated mountain range in a sea of desert, the La Sals gets hammered by the wind and weather and can be unpredictable. In upper elevations, the mountain faces are steep and intimidating. Low angle, forested slopes are few and far between. Despite being a relatively small mountain range — there are only 12 major peaks in the La Sals — the terrain is difficult to navigate. The locals like to say you have to ski uphill both ways.

But the real reason for the La Sals’ infamy is the snowpack. The mountains in southern Utah get much different and much less snow than the north, resulting in wildly unstable avalanche conditions.

“It’s a shallow snowpack,” said Eric Trenbeath, forecaster for the Utah Avalanche Center’s Moab Office. “A shallow snowpack is a weak snowpack.”

Referred to as a continental snowpack, avalanche conditions in the La Sals are often more in line with the Colorado Rockies rather than the Wasatch Range. The shallow snowpack loses heat at a faster rate, causing water vapor to transfer up and essentially ‘rot’ the bottom layer of snow. This creates a weak, faceted bottom layer that usually cannot sustain much weight. When the snow starts to pile up on that weak layer, the La Sal’s can unleash massive avalanches.

During the 2018-19 season, this effect was on full display. As the winter ended, the La Sals received 200% of their average annual snowfall, which — combined with a widespread persistent weak layer — resulted in some of the most dangerous avalanche conditions the mountain range has seen in years. One historic natural avalanche off the west face of Mount Tukuhnikivatz decimated hundreds, possibly thousands, of trees, carving out a path of destruction visible from Moab’s Main Street.

Sadly, this historically dangerous winter cost one snowmobiler his life. The group from Monticello headed into the Dark Canyon area of the La Sals in the afternoon of January 26, riding through feet of powder on their way up to the alpine. Around 4:00 p.m., one man rode up a narrow gully near Laurel Peak. Three other riders followed, and as the first rider reached the top of the slope, an avalanche roughly 1,000 feet wide broke off below him.

While two of the snowmobilers were able to veer out of the way of the barreling slide, the third caught the avalanche head on. The group began searching frantically but were only able to find the rider’s helmet and snowmobile. One of the riders called 911, but with light fading in the late afternoon, search efforts were called off until the following morning.

The next day, search and rescue teams were able to locate the rider’s body about 150 feet from where his snowmobile had been found. Although he had left home with an avalanche beacon, it was turned off in his backpack.

“We aim to learn from accidents like this and in no way intend to point fingers at victims,” the UAC stated in a report published shortly after the accident. The group had three avalanche beacons, two shovels and one probe spread out among eight people.

It’s impossible to know if the tragedy could have been averted had all riders been properly equipped with avalanche gear. Regardless, the accident serves as a grim reminder to never go into the mountains without a working beacon, shovel and probe.

The avalanche danger that day was also rated as “considerable” by the UAC, advising backcountry goers to steer clear of East-facing slopes, like those in Dark Canyon where the fatality occurred. “In the end, we’re making general travel advice for people,” Trenbeath said, who published the forecast that day.

And even when the avalanche rating is low, the danger is still there. “One of the favorite phrases for avalanche forecasters is ‘low danger doesn’t mean no danger,’” Trenbeath said, recalling an accident a few years prior where a man was caught in an avalanche on a low danger day. The skier broke his kneecap after triggering a slide that carried him over rocks.

“I would still call it low danger to this day,” Trenbeath said about the incident, stressing that terrain choices are key to staying safe. “You always need to recheck and reassess anytime you’re dropping into avalanche terrain.”

A former ski patroller at Alta Ski Area, Trenbeath has been with the UAC since 1999 and has seen substantial growth in Moab’s once fledgling backcountry community. “I would sometimes be the only person out there,” he said, remembering when he first started forecasting for the Moab Office 20 years ago. Now he has a reliable crew of paid observers, gathering information to help him post a daily avalanche forecast on the UACs website.

Trenbeath’s typical day starts at 5:30 a.m. He begins by compiling information from other observers’ forecasts in the region, as well as information collected from his own personal field days. By 7:30, he publishes the forecast on the UAC’s website, then checks in again with his observers to see how the weather that day is affecting the snowpack. Then around 9:00, he jumps in his Forest Service truck, and heads up into the mountains.

“It’s a great job…but it’s a lot of work,” said Trenbeath, who is lucky to get home by 5:30 p.m. most days. While the UAC’s Salt Lake location has more resources and staff, the Moab office is a one-man show. In addition to posting a daily avalanche forecast, Trenbeath teaches backcountry safety classes, sets up signs, beacon parks (areas for backcountry skiers to practice rescue techniques) and more.

Trenbeath’s hard work allows skiers in the greater Moab area to head into the mountains with a solid understanding of recent weather events and changes in the snowpack, and this information can lead to potentially life-saving decisions. Since 2010, two people have died from avalanches in the La Sals. Without Trenbeath’s forecast, this number could be much higher.

“You feel some responsibility for sure…you want to give people the best advice that you can and do your best to make an accurate forecast,” Trenbeath said.

Remember, low danger doesn’t mean no danger. But if the conditions are right, an unparalleled backcountry experience is waiting in the La Sals. Views from the top of any of the 12 main peaks are arguably some of the most amazing and unique in the entire country, with the jagged San Juan mountains to the East, the Abajo mountains to the south, and a winding maze of red desert everywhere in between.

Breathtaking views aside, the skiing in the La Sals is some of Utah’s best. Most backcountry skiers access the mountains from the Geyser Pass trailhead, which boasts the highest elevation of any winter trailhead in Utah. The approaches are long, and if you’re used to backcountry skiing in places like Grizzly Gulch or Beartrap Fork in the Central Wasatch, you might be in for a rude awakening. There isn’t much terrain where you can ski directly back to the car and most exits will require you to put the skins back on and hike out — but that’s all part of the fun.

At 12,482 feet, Mount Tukuhnikivatz — nicknamed Mount Tuk—is one of North America’s 50 classic ski descents. Accessed by way of the Geyser Pass trailhead, Mount Tuk features 3,500 vertical feet of amazing skiing. Neighbored by Mount Peele, Mount Laurel and Mount Mellenthin, an avid backcountry skier could happily camp out at the Geyser Pass trailhead for months. On a high danger day, when the big peaks and cirques are off-limits, the trees off of Laurel Ridge offer both fun low angle skiing and amazing scenery.

Regardless of where you go, the solitude found in the La Sals is refreshing, especially for anyone that skis in the Central Wasatch. Although Moab’s ski community is growing, the tricky terrain and remoteness of the La Sals makes the range a great place to ditch the crowds. Even on the sunniest of spring days, the trailheads and skin tracks are nowhere near as busy as Little and Big Cottonwood Canyons.

“I feel really fortunate to have this alpine mountain range in the middle of the desert,” Trenbeath said, speaking over the phone after publishing the day’s avalanche forecast. “There’s not a day I go up there without my camera…it just blows my mind every time.”