Zen and the Art of Ropework

If one of your classmates is into adventure sports, you can probably tell from across the lecture hall. Laptops, water bottles, and cars layered with so many stickers, you can’t really be sure what color the substrate is.

Normally I’m too much of an anarchist to eagerly provide free advertising for a corporation, yet I’ve marked my car with stickers and my skin with ink. With three hundred feet of air between me and the ground, hanging on an 11 mm rope felt like hanging on a strand of dental floss. An acute awareness of every piece of equipment preventing death or life altering injury forms a strange relationship between someone and their gear. It would be more surprising if we weren’t a little ritualistic, superstitious, or even evangelical. This brand of carabiner saved my life, and it can save yours too! This rappel device took me to one of the coolest places I’ve ever been, you should check it out! Let the stickering commence.

Normally I’m too much of an anarchist to eagerly provide free advertising for a corporation, yet I’ve marked my car with stickers and my skin with ink. With three hundred feet of air between me and the ground, hanging on an 11 mm rope felt like hanging on a strand of dental floss. An acute awareness of every piece of equipment preventing death or life altering injury forms a strange relationship between someone and their gear. It would be more surprising if we weren’t a little ritualistic, superstitious, or even evangelical. This brand of carabiner saved my life, and it can save yours too! This rappel device took me to one of the coolest places I’ve ever been, you should check it out! Let the stickering commence.

At the beginning of a challenging section of river, I wade out into the water and face upstream, then unbuckle and remove my helmet. I fill my helmet with cold river water before I pour it over my head and face. My larynx spasms, my body tries to prevent itself from drowning, I gasp for air, water pours from my hair and beard. When I put my helmet back on, water drips out of the liner and down my face, and I’m ready to paddle.

Before canyoneering and caving trips, I usually have anxious moments. Sitting down with my gear and harness, I methodically go through my descending system, my ascending system, and my rescue gear, stowing it on the appropriate gear loops. I’ve prepared for the challenges I know we’ll face. Some preparation has been made for little surprises or emergencies, but I also have to accept there’s no reasonable way to be prepared for everything. Should the Earth be hit by a comet, we’ll do the best we can with what we have. This act of preparing, and considering what emergencies might arise, helps me feel better.

Watching skydiving instructors pack their parachutes, I was struck by their focus. They were silent, intent, and methodical, much like martial artists presenting their forms. Perfectly choreographed, and flawlessly executed.

A pilot performing their preflight checklist, my Mom starting an IV on a patient, even the way I make coffee in the morning, all have some interesting similarities. One of the main ones is we could almost, if not literally, do it with our eyes closed.

Sometimes, adhering to the same routine every time helps avoid errors, and insure small but potentially details aren’t missed. Most of these rituals serve a very practical purpose. Splashing cold water in my face stimulates the mammalian diving reflex, and when I’m hit with cold water, it’s less of a shock. Hopefully this lets me focus on keeping the boat upright, or focus on swimming the rapid if I’m less lucky. Double checking the gear on my harness makes it less likely I’ll forget something important. When Mom starts an IV, so much of the process is automatic, her mind is free to focus on finding and sticking the vein. I could probably brew a cup of coffee with my eyes closed, in my sleep. Maybe I already have.

By the time my coffee’s done, sometimes I feel like I don’t even need it. Something about the process, weighing and grinding the beans, heating the water, helps reunite my conscious self, my body, and this world we find ourselves in. It’s no coincidence ritual is a crucial element of so many faiths. Clearly, it’s important to us as humans. What I find fascinating is how similar these rituals are to the ones more traditionally practiced in a church or temple.

By the time my coffee’s done, sometimes I feel like I don’t even need it. Something about the process, weighing and grinding the beans, heating the water, helps reunite my conscious self, my body, and this world we find ourselves in. It’s no coincidence ritual is a crucial element of so many faiths. Clearly, it’s important to us as humans. What I find fascinating is how similar these rituals are to the ones more traditionally practiced in a church or temple.

Ritual and meditation go hand in hand. Some would suggest if ritual isn’t essential to meditation, it certainly helps. In my own experience, and in conversations with others, in adventure sports we find moments of peace and calm under conditions most people would find terrifying, not serene.

My senior year of high school was not an easy time in my life. I was struggling with some family problems, my faith, and my sexuality. On the ground, I was full of stress and panic. Fortunately, I was working on a pilot’s license. During those hours in the air, I was so completely focused on keeping my bird in the air, all my problems were left behind on the ground.

One of my friends told me some of the best climbing he’s done has been when he was mentally at his worst. Ironically, descending into the deepest canyons and caves has helped me rise above my day to day challenges.

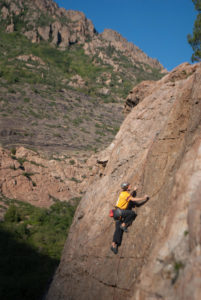

Another friend has talked about how free he feels lead climbing, especially during a challenging semester. When he’s struggling with a hold on a difficult route, trying to avoid a fall, he’s not worried about a midterm, work tomorrow, anything other than himself and the wall.

Another friend has talked about how free he feels lead climbing, especially during a challenging semester. When he’s struggling with a hold on a difficult route, trying to avoid a fall, he’s not worried about a midterm, work tomorrow, anything other than himself and the wall.

All things in moderation, they say. Any way to escape your stress and problems can become a problem. Although being an “adrenaline junkie” probably isn’t as unhealthy as a drug or alcohol problem, it can be problematic. In my own experience, I spend a little too much time avoiding my problems. Between river trips, canyon trips, cave trips on the weekend, volunteering with an ambulance department, an internship, a job, classes, it’s more than a body can handle.

Excitement and adventure and really wild things serve as an excellent break from the day to day. Any therapist (physical or mental health) will probably tell you we all need rest. The best way to insure we can spend more time in our favorite places doing our favorite things is to make sure we make time to relax and recover.

In the future, I suggest watching yourself and your friends. Where does this sort of ritual and meditation fit into your life and adventures? How much is something essential, like making sure life support equipment is secure, and how much is tradition, something serving no obvious purpose, but you feel better for having done it? Most of us put our pants on one leg at a time, but I’m guessing we start with the same leg every time.

Alex Chagovetz

Nov 27, 2021 at 12:30 pm

Great write up John. I have also found rope work to be rather meditative!